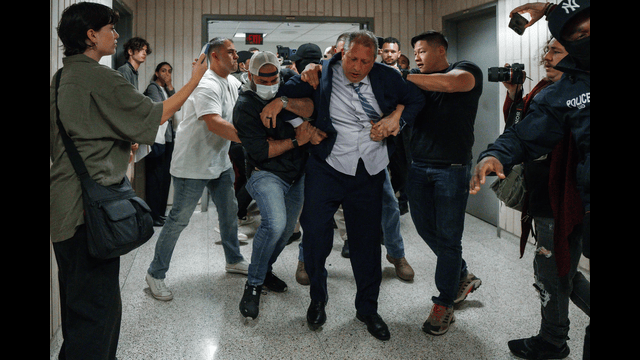

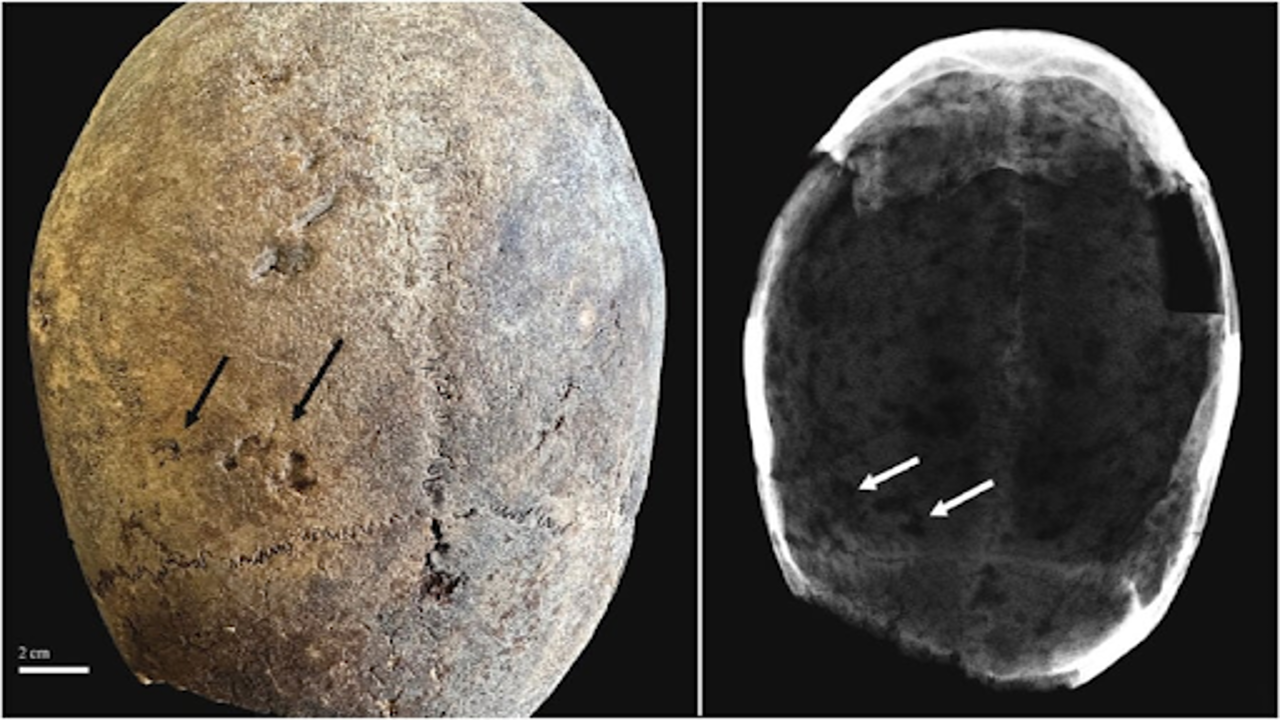

Brain tissue was collected from skulls found in a crypt near a famous hospital. However, it's unlikely that cocaine was used as a treatment for illnesses. Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science

A surprising discovery has emerged from a recent study by Italian researchers, revealing that preserved brain samples from early 17th-century Milan contain traces of cocaine. This finding challenges the long-held belief that cocaine only became prominent in Europe in the 19th century, a time famously marked by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud's promotion of the drug. The discovery suggests that the use of cocaine in Europe might have started nearly 200 years earlier than previously thought.

The study was conducted by a team from the University of Milan, who examined brain samples from mummies found in the Ca' Granda crypt of the Ospedale Maggiore, a historic Milanese hospital and church complex. The crypt, dating back to the late Renaissance, holds an extensive collection of human remains, with an estimated 2.9 million bones representing over 10,000 individuals from that era.

Researchers performed toxicological tests on nine brain samples and discovered that two of these samples contained traces of cocaine and related substances. This finding is perplexing because historical records from the hospital do not mention the use of cocaine or its presence in their medicinal practices.

The origin of cocaine is from the Erythroxylum coca plant, native to South America. Indigenous cultures, including the Inca Empire, used coca leaves for various purposes such as medicine and religious rituals. The plant's effects included reducing hunger and thirst, providing a sense of well-being, and enhancing physical performance.

During the colonial era, Spain tightly controlled the coca trade, making it difficult for the plant and its derivatives to reach Europe. The journey across the Atlantic often damaged or destroyed the coca shipments, limiting the drug's presence in Europe.

It wasn't until the 19th century that cocaine, in the form of chemically synthesized hydrochloride salts, became widely known in Europe for medicinal and recreational use. Despite this, the Milanese mummies suggest that cocaine's use might have started earlier, though the exact method of its introduction remains unclear.

The discovery of cocaine in these early European remains could be linked to the period's extensive maritime trade routes. Milan, under Spanish rule during the 17th century, was a significant trade hub and might have received exotic plants and substances from the Americas. The researchers hypothesize that the cocaine found in the mummies could have been used recreationally or as a productivity enhancer, similar to its use among Spanish colonists in the New World.

To ensure the accuracy of their findings, the researchers carefully handled the brain samples to avoid contamination. They found trace amounts of hygrine, a compound associated with coca leaves, but not with modern cocaine salts, supporting the idea that the drug was used in its more natural form rather than as a purified substance.

The study highlights the need for further investigation into the early use of coca products outside the Americas. The presence of cocaine in these mummies opens up new discussions about the spread of this drug and its uses in pre-modern Europe.