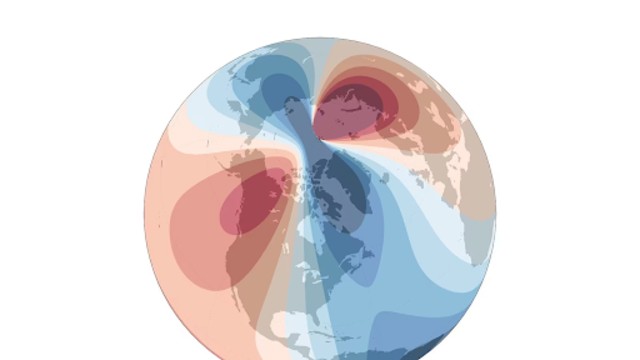

This image illustrates magnetic declination, which is the angle between magnetic north and geographic north, based on the World Magnetic Model released in 2025. The red area shows magnetic north to the east of geographic north, while the blue area indicates magnetic north to the west. CNN

In a significant update for navigation systems, scientists have released new data on the movement of Earth's magnetic north pole. The pole is now closer to Siberia than it was five years ago and continues to drift toward Russia. This update is vital for systems like GPS, which rely on the position of magnetic north for accuracy. The new findings mark the ongoing changes in Earth's magnetic field, which have been increasingly unpredictable in recent years.

Unlike the fixed geographic North Pole, the magnetic north pole is determined by Earth's dynamic magnetic field, which is constantly in motion. In recent decades, this movement has been faster than usual. After speeding up dramatically in the 1990s, the magnetic north pole’s drift recently slowed down, though scientists are still unsure of the exact reasons behind this erratic behavior.

Global Positioning Systems (GPS), used by ships, planes, and even smartphones, rely on the World Magnetic Model (WMM), which has been updated every five years to adjust for the magnetic north's shifting position. The WMM was developed in 1990 by a collaboration of the British Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It helps predict where magnetic north will be, based on past movements.

The latest WMM update was released on December 17, 2024, and includes two models: the standard WMM, with a spatial resolution of about 3,300 kilometers at the equator, and a high-resolution version with much finer accuracy, down to 300 kilometers at the equator. The high-resolution model, though more precise, is mainly useful for experts and specific uses like aviation. For everyday users, the standard model is sufficient.

Dr. Arnaud Chulliat, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado, explained that updates like this are essential for ensuring GPS systems remain accurate. "The more you wait to update the model, the larger the error becomes," he said. With the new model, scientists confirmed that the previous model's predictions about the magnetic north pole's position by 2025 were accurate.

The magnetic north pole’s movement is not a recent phenomenon. The geographic North Pole, the "true north" fixed at the Earth's top, contrasts with the magnetic north pole, which changes because of the shifting magnetosphere—the area around the Earth affected by its magnetic field. Discovered in 1831 by Sir James Clark Ross in northern Canada, the magnetic north pole has gradually moved toward Russia over time. By the 1940s, it had already drifted about 250 miles northwest. In 2000, it left Canadian shores entirely.

What makes this shift so notable is the rapid acceleration of movement that began in the 1990s. The magnetic north pole started moving at a speed of 34 miles per year, much faster than the typical 10 kilometers per year. Around 2015, the movement slowed to 21 miles per year. This unpredictable behavior prompted scientists to update the WMM earlier than planned in 2019.

Looking ahead, experts predict that the drift toward Russia will likely slow further, but the rate of change is uncertain. Dr. William Brown, a geophysicist at the British Geological Survey, mentioned that the speed of the drift could change again, either accelerating or decelerating. However, there is no expectation for another update before 2030.

While Earth's magnetic field is known to undergo dramatic reversals over long periods of time, these flips are rare and take thousands of years to complete. The last such reversal occurred around 750,000 years ago, and it could have serious impacts on technology. For example, it could disrupt animal navigation, affect radio communications, and put satellites at risk.