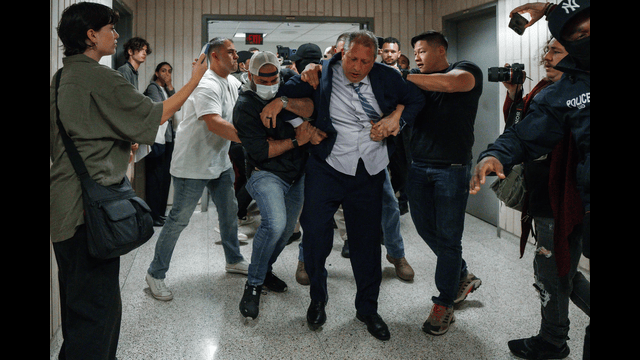

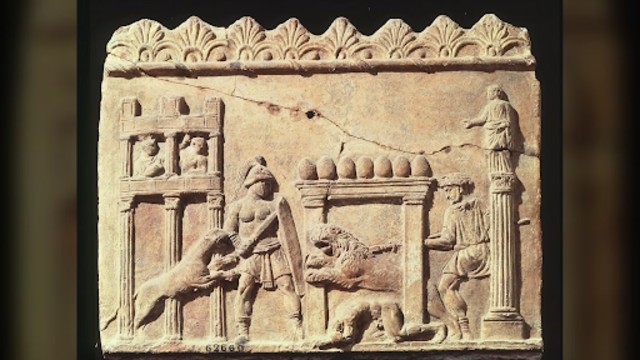

A piece of Roman artwork from the first century shows a warrior battling a lion. CNN

A fascinating discovery in York, England, has given researchers new insights into ancient Roman combat. Archaeologists have found a skeleton that could be the first physical proof of gladiators fighting animals, like lions, for entertainment. This remarkable find was made in a Roman-era cemetery and has been described as a rare and exciting glimpse into the brutal world of gladiatorial contests.

The man’s remains, estimated to be between 26 and 35 years old when he died, were buried in a grave about 1,825 to 1,725 years ago. His bones show clear signs of a fierce encounter with a large cat, likely a lion. The bite marks, found on his pelvis, suggest a deadly attack, which researchers believe led to his death. This discovery provides the first tangible evidence of such violent battles taking place outside of Roman arenas like the Colosseum in Rome.

The remains were found in a place known as Driffield Terrace, which archaeologists call a "gladiator graveyard." This site lies along an old Roman road out of York. In 2010, a documentary revealed the discovery of 82 skeletons of young, strong men in the same area, all showing signs of intense physical training and injuries, leading researchers to believe they were gladiators. The presence of the bite marks on this specific skeleton, however, now confirms the gladiator's involvement in animal combat.

For years, researchers relied mostly on ancient texts and artwork to understand gladiatorial games, where men fought animals. But there was little physical evidence to back up these accounts. Tim Thompson, the lead author of the study, shared his excitement about the discovery: “This find reshapes our understanding of Roman entertainment, showing it was not just in Rome but across the Empire, even in faraway York.”

Scans and studies of bite marks on the pelvis showed they were likely made by a large cat, probably a lion, after comparing them with the teeth marks of different carnivores. CNN

The men buried at this site likely came from various parts of the Roman Empire, judging by their diverse origins. Some skeletons show signs of injuries from training or battles, while others have unique burial rites, like decapitation. The man with the lion bite, for example, suffered from other health issues, including malnutrition and spinal problems, which were likely due to his demanding life as a gladiator.

When researchers analyzed the bite marks on the skeleton, they compared them with those of different carnivores, including lions. The bite marks were identified as being from a large cat, and further analysis confirmed the skeleton's identity as a gladiator who fought beasts in the arena, known as a “bestarius.” This gladiator, like others, could have been a slave or a volunteer. If he survived his brutal fight, he could gain fame or even buy his freedom.

Interestingly, the bite marks never healed, which suggests they contributed to his death. Researchers also believe he was decapitated after death, which was sometimes done as a merciful gesture or part of Roman burial rituals. Barry Molloy, an expert in archaeology, noted that gladiators were seen as athletes, and their owners would want them to survive, as they brought in the crowd’s excitement.

This discovery is also significant because it shows the reach of Roman culture across Britain. The presence of lions in York indicates that gladiator games involving animals were common, even far from Rome. York, once known as Eboracum, was a major Roman city, and gladiatorial events may have continued there until the Roman Empire’s decline in the early fifth century.

The find also sheds light on the logistics of transporting exotic animals, like lions, from places like Africa to Roman Britain. Dr. John Pearce, one of the study’s authors, explained that these animals would have been transported along well-established routes.

In conclusion, this discovery not only offers a glimpse into the life and death of a gladiator but also highlights the widespread nature of Roman entertainment. The gladiators, and the animals they fought, were part of a larger spectacle that was central to Roman culture, even in places like York.