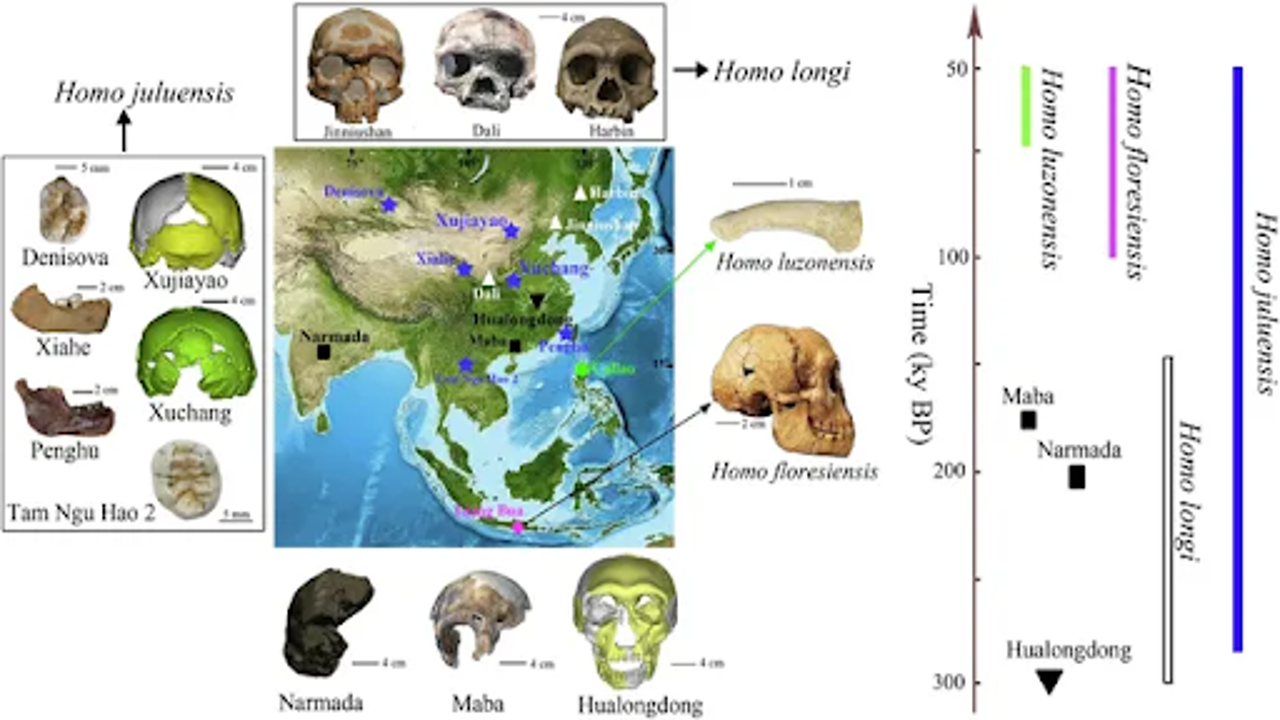

A diagram illustrates the locations of ancient human sites in central Asia, highlighting the fossils found at these sites. Live Science

Researchers have recently uncovered a new species of ancient humans, named Homo juluensis, or "big head people," based on fossils discovered in China. This exciting discovery adds to our understanding of human evolution, particularly during the Middle Pleistocene period, about 300,000 to 50,000 years ago.

For years, scientists have struggled to comprehend the evolution of early humans before the emergence of modern Homo sapiens. After modern humans began to spread out of Africa around 300,000 years ago, many other hominin species lived on Earth. Among these were species like H. heidelbergensis and H. longi, though not all experts agreed on whether these fossils represented distinct species. As a result, terms like "archaic Homo" and "Middle Pleistocene Homo" have been used, but these catch-all labels have limited the clarity of the evolutionary relationships among our ancient ancestors.

In a study published in May 2024 in PaleoAnthropology, a team led by Christopher Bae, an anthropologist at the University of Hawai'i, and Xiujie Wu, a paleoanthropologist from China, described a collection of unusual hominin fossils found decades ago at Xujiayao, located in northern China. The most striking feature of these fossils was the unusually large skulls, some of which shared Neanderthal-like features while also resembling traits of modern humans and Denisovans. These findings led the researchers to propose that the fossils belonged to a previously unknown hominin species, which they named Homo juluensis, referring to "big head" people.

The fossils found at Xujiayao and other locations, like Xuchang in central China, date back between 220,000 and 100,000 years ago. Excavations in the area, such as the 1974 discovery of more than 10,000 stone artifacts and fossil fragments from at least 10 individuals, showed that these ancient humans had large brains and thick skulls. The skulls from Xuchang closely resembled those of Neanderthals, further supporting the idea that H. juluensis shared characteristics with other ancient human species.

While H. juluensis is a new species, the researchers believe these hominins were not entirely isolated. Instead, they might have interbred with other Middle Pleistocene species, including Neanderthals. This suggests that hybridization played a significant role in shaping human evolution in East Asia.

Though H. juluensis is not universally accepted in the scientific community, it is gaining support. Some experts argue that the fossils may better align with H. longi, a species discovered in central China. For example, paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London believes that large skulls alone are not a sufficient trait to define a new species. However, he acknowledges that the Neanderthal-like characteristics of some fossils, such as those from Xuchang, make their classification more complicated.

Ultimately, naming H. juluensis helps clarify the fossil record and the evolutionary history of humans in Asia. Bae believes that this new name will improve the communication of findings in evolutionary biology and anthropology, providing a clearer picture of humanity’s ancient past.