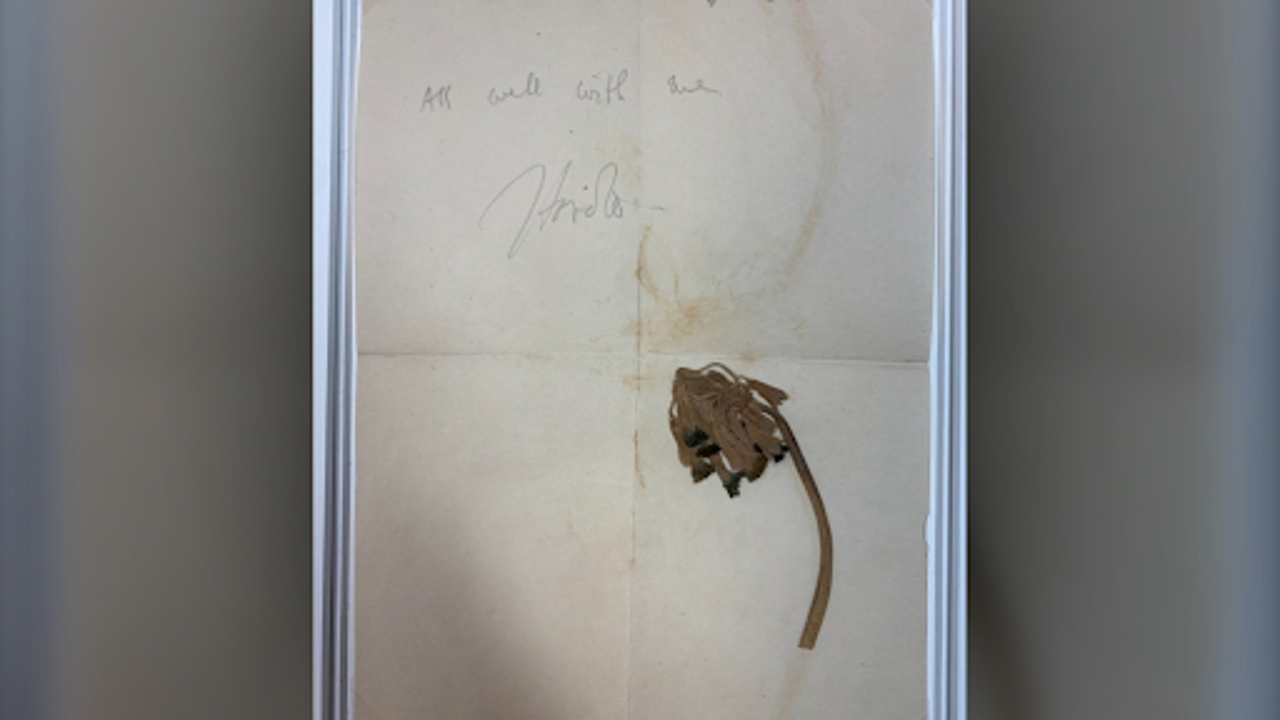

A 1916 letter from soldier Harold Wrong sent to his brother in Toronto included a flower, that until recently, had not been identified.

On June 30, 1916, Harold Wrong picked a flower from a field in Somme, France, and placed it in a letter to send back home to Toronto. He wrote simply to his brother, “All well with me.”

The next day, he was killed during the first day of the Battle of the Somme, just after being seen heading over the top of a trench despite having a wounded arm.

A University of Toronto graduate, Wrong had joined the Lancashire Fusiliers while studying at Oxford University. His father worked at the university, and his grandfather had been the second premier of Ontario. Decades later, in the 1960s, the letters he sent home to his family were donated to the university’s library. Yet for years, the flower Harold included in his letter remained a mystery.

Loryl MacDonald, the University of Toronto’s associate head librarian, explains that more than 24,000 Canadians lost their lives during the Somme offensive in the summer of 1916, making Harold’s letter all the more poignant. “This letter humanizes Harold and places us right there in the trench with him,” she says.

Harold Wrong, seated and holding a newspaper, appears in an undated photograph. Wrong, a Canadian, was killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. (Supplied)

For years, MacDonald speculated that the flower might have been a blue cowslip, but there was one issue: the flower blooms in early spring, while Harold had mailed his letter in late June.

In early September, new technology provided some answers. Researchers at the university used multi-spectral imaging, a technique that captures images using different types of light to reveal details invisible to the naked eye. The team studied more than a dozen rare materials from the university’s archives, including the flower Harold had sent home.

Jessica Lockhart, head of research at the school’s Old Books, New Science lab, explains, “We were able to use the UV spectrum to see more details of the flower’s casing, and the original bloom that had withered and changed its shape as it aged.”

With help from botanists and old photographs, the team confirmed that the flower was indeed a blue cowslip.

While it may seem like a small detail, historians believe such discoveries offer vital insights into history. “The experiences people went through during World War I are getting farther away from us,” Lockhart says. “If we want to retain the lessons of the past and understand the lives of those who came before us, we need to revisit the records and stories of that time.”

The technology used to uncover the mystery of Harold Wrong’s flower could also shed light on other historical documents. Researchers are already using it to help date an ancient Jewish manuscript, which may turn out to be the oldest of its kind in the world.