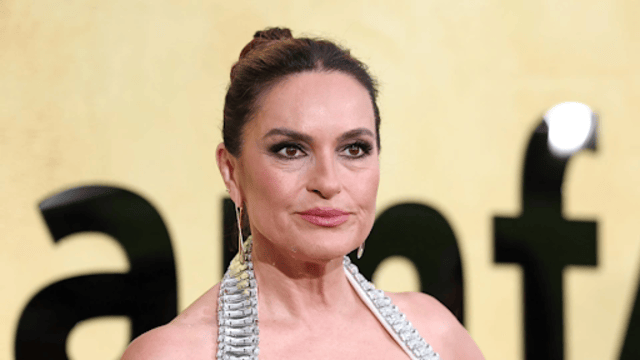

A Japanese attendant serves sake to visitors at the Koami Shinto shrine. CNN

In Japan, while whisky, nihonshu (sake), and beer have gained international popularity, there’s a lesser-known drink making a slow comeback—doburoku. This ancient, unfiltered sake has a unique history and is now being reintroduced to both locals and tourists at a special bar in Tokyo.

Nestled in the upscale Nihombashi neighbourhood, Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery is taking the lead in reviving this drink. The brewery, which has been crafting sake since 1928 in Wakayama Prefecture, chose this location because it thrived during the Edo period (1603-1868) when boats frequently transported sake in the area. The brewery’s decision to open a doburoku bar in such a historic district highlights the drink’s significance in Japanese culture.

So, what exactly is doburoku? The drink's murky history mirrors its cloudy appearance. Often regarded as a precursor to modern sake, doburoku is noted for its unrefined nature. The name itself means “cloudy liquor,” and it stands apart from the clearer, more refined sake. The production methods differentiate these drinks significantly.

Making typical sake involves a careful process where a yeast starter, called shubo, is added to steamed rice, koji (a rice fungus), and water over several days. In contrast, doburoku combines all ingredients at once. This method results in a sweeter beverage with lower alcohol content because fermentation halts earlier due to an overload of sugars.

Doburoku’s history is steeped in tradition and has been enjoyed for centuries. It was commonly consumed by farmers and Shinto priests, who appreciated its straightforward brewing method. For a long time, homebrewing was prevalent, and in 1855, Tokyo alone had nearly 460 doburoku producers. However, everything changed with the establishment of the Meiji government, which sought to regulate alcohol production. New laws began to restrict homebrewing, culminating in a complete ban on it in 1899. After this, doburoku became known as “secretly produced alcohol” or moonshine.

Despite these restrictions, doburoku continued to be made, especially at Shinto shrines for ceremonial purposes. After World War II, due to a sake shortage, an unfiltered Korean drink called makgeolli became a popular substitute. A significant change occurred when the Japanese government allowed certain inns and restaurants in deregulated zones to sell doburoku commercially, starting in 2003. As of 2021, there were only 193 licensed establishments across Japan.

The journey to revive doburoku in Tokyo began in 2015 when Sake Hotaru opened as the first legal spot to serve the drink. By late 2016, it was officially available to the public. Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery followed suit in June 2022, attracting a diverse crowd, with about half of its visitors coming from abroad. Norimasa Yamamoto, the brewery's president, has noted that many patrons are curious about how doburoku differs from sake and its production process.

At the brewery, visitors can also sample the brewery’s sake and beer, although it’s important to note that cash is not accepted for purchases. The taste of doburoku is described as intense, with some drinkers likening it to flavours such as cheddar cheese or the Polynesian noni fruit. For those unable to visit Japan, Kato Sake Works in Brooklyn offers small batches of doburoku, though the drink is still relatively unknown in the U.S.

Doburoku’s unique character and rich history make it a fascinating beverage that reflects Japan's evolving drinking culture. As more people discover this traditional brew, doburoku is poised to reclaim its place in Japan’s vibrant landscape of alcoholic beverages.