Spider keeper Emma Teni in her office at the Australian Reptile Park…

In a quiet corner of the Australian Reptile Park, Emma Teni grips a spider with pink tweezers. The creature, a Sydney funnel-web, rears its legs. That’s her cue. With a steady hand, she extracts venom from its fangs using a small pipette.

It’s part of a life-saving process—one that turns deadly venom into powerful antivenom. It may sound strange, but Australia’s most dangerous animals are also its silent saviors.

Inside the Spider Milking Room

Emma works in what’s known as the spider milking room. It’s lined wall-to-wall with containers of spiders. A thick black curtain keeps them calm, while a viewing window lets curious visitors peek in.

Each day, she milks around 80 funnel-webs. These spiders are no joke. Their venom is among the most lethal in the world. Without quick treatment, a bite could kill within minutes.

How Antivenom Has Changed the Game

Since 1981, no one has died from a funnel-web spider bite. That’s thanks to the park’s antivenom programme. But it doesn’t work alone. Locals play a key role by catching spiders and delivering them to drop-off points.

Emma and her team travel across Sydney weekly in a van covered in crocodile decals. They collect spiders found in backyards, sheds, or even inside homes.

One such helper is Charlie Simpson. After spotting a funnel-web in his garden, he caught it wearing gloves and handed it over. “Their fangs are huge,” he says. “But I knew it could help save a life.”

Every Spider Counts

Each spider brought to the park is logged, sexed, and sorted. The males—far more toxic than females—are used in the antivenom programme. They’re milked every two weeks.

It takes venom from 200 spiders to make just one vial of antivenom. The process is delicate. The venom is collected drop by drop using a suction pipette.

Emma, who once studied marine biology and worked with seals, now embraces her title of “spider girl.” Her love for arachnids is so well known that people leave spider jars at her doorstep.

The Snake Room: Another Frontline in Venom Research

Just steps away, another team handles reptiles even more feared—snakes. Billy Collett, the park’s operations manager, handles a King Brown snake with ease.

He collects its venom using a glass and cling film. A single bite could kill multiple people, yet Collett calmly reassures: “They don’t want to bite you. We’re too big to eat.”

From Venom to Cure: The Science Behind the Serum

To produce antibodies, animals are key. Horses receive small doses of snake venom. Rabbits take spider venom. Over time, they develop immunity.

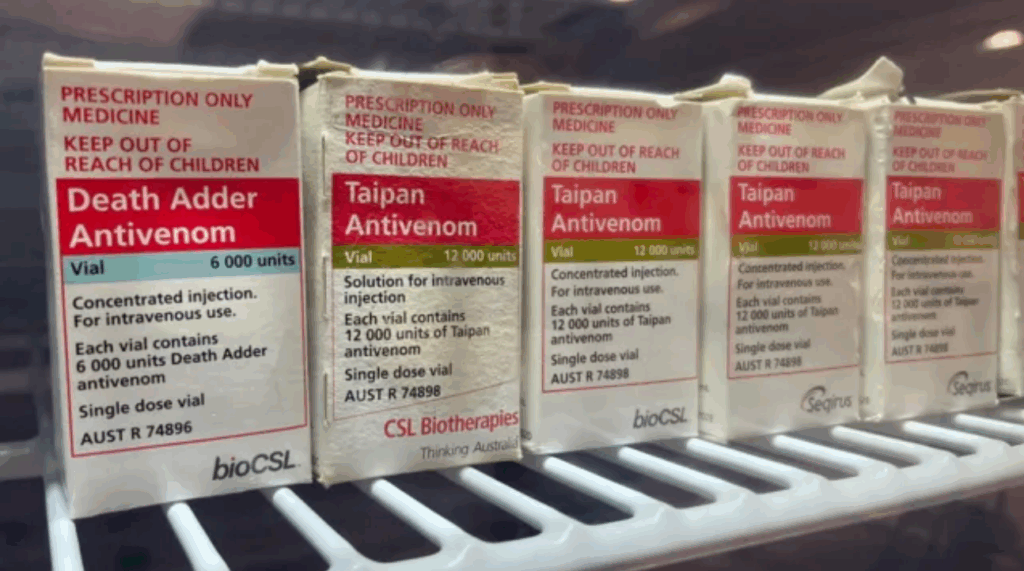

Blood is then collected and processed to extract plasma rich in antibodies. These are bottled into antivenom vials—up to 7,000 each year for a range of venomous creatures.

Each vial has a shelf life of 36 months and is distributed across Australia. Placement is strategic, depending on which species are common in which region.

Global Impact: Saving Lives Beyond Australia

Antivenom isn’t just used locally. Around 600 vials are sent to Papua New Guinea annually, a country with high snakebite rates.

Australia shares many snake species with its neighbor due to an ancient land bridge. The free supply is a form of “snake diplomacy,” says Chris Larkin of CSL Seqirus. It's estimated that over 2,000 lives have been saved there thanks to the programme.

A Safe Place for a Dangerous Encounter

Despite their reputation, Australia’s deadly creatures are not out to get you. Most bites happen when humans try to kill or handle them.

“If you’re going to be bitten,” jokes Collett, “Australia’s the best place. The treatment is world-class—and it’s free.”

In a land where danger crawls and slithers, venom has become an unlikely hero. And thanks to science—and a bit of bravery—Australia is turning deadly into lifesaving.