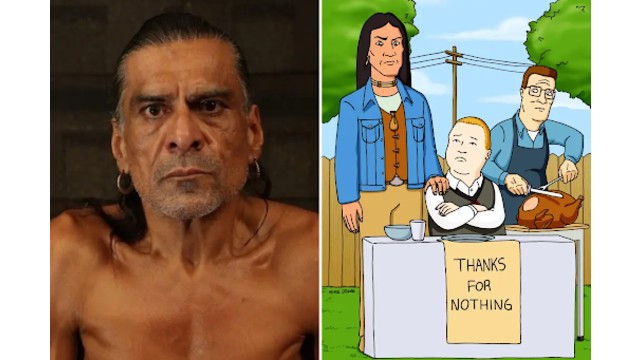

College students from various nearby schools march down Commonwealth Avenue in Boston on Oct. 16, 1965 to attend rally on Boston Common protesting U.S. involvement in Vietnam. They're hallmarks of American history: protests, rallies, sit-ins, marches, disruptions. They date from the early days of what would become the United States to the sights and sounds currently echoing across the landscapes of the nation's colleges and universities. (AP Photo)

Fifty years have passed since the end of the Vietnam War. But the music of that era still sings.

For legendary folk singer Judy Collins, one performance from those days remains unforgettable.

“It was just me, and Bruce Langhorne playing the guitar, for this huge event. ... And everybody knows the words and very quickly they all start singing along,” she says, remembering the “amazing” spirit of those rallies. “It does trigger something in the brain to hear those songs. They make you say, ‘I must be able to contribute something.’"

The Golden Era of Protest Anthems

In the 1960s and 70s, Collins joined forces with Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, and Peter, Paul and Mary.

They traveled the country, using their music to demand an end to war and inequality.

Songs like Give Peace a Chance, Blowin’ in the Wind, and We Shall Overcome became rally cries.

Crowds didn’t just listen. They sang along, making the music part of the movement itself.

Those songs echoed far beyond protests. They climbed the Billboard charts and reached mainstream audiences.

They were part of a bigger cultural wave — one fueled by post-war optimism and civil unrest.

A Shift in the Soundscape

Today, protest songs still exist, but few strike the same cultural chord.

Ginny Suss, co-founder of the Resistance Revival Chorus, believes it’s because today’s landscape is decentralized.

“Genres and identities are more spread out,” she explains. “We don’t have that same collective experience.”

Sociologist Ronald Eyerman agrees. He points out that recent songs are issue-specific and lack universal appeal.

“There hasn’t been a We Shall Overcome for climate change or LGBTQ+ rights,” he notes.

Voices of Resistance Around the World

While the U.S. may lack a dominant protest anthem, international artists are filling the gap.

Iranian singer Mehdi Yarrahi risked punishment to sing Roosarito, urging women to remove their headscarves.

Indonesia’s punk band Sukatani fired back at corruption with their song Bayar Bayar Bayar.

Puerto Rican rapper Residente uses his platform to tackle war, colonization, and inequality.

His track Bajo los Escombros, made with Palestinian artist Amal Murkus, honors children killed in Gaza.

“There aren’t many songs talking about it,” he says. “But that’s why we sing them.”

A Hesitant Industry

Bill Werde, music industry expert, believes today’s climate makes artists wary of protest themes.

“Most artists, like corporations, avoid politics — it’s risky for business,” he says.

Even Lamar’s Super Bowl performance had to be subtle enough for sponsors to sign off on.

Yet protest songs occasionally break through. During the George Floyd protests, tracks like Alright and This Is America gained traction.

Still, they were responses to tragedy, not widespread anthems of a united movement.

When Protest Songs Lose Their Meaning

Many iconic songs are now stripped of context and repurposed.

Fortunate Son, once an anti-war anthem, played at Trump rallies and in jeans commercials.

Blowin’ in the Wind was used to sell Budweiser during a Super Bowl.

TikTok users dance to Zombie without knowing it’s about the Troubles in Ireland.

“Music lives on fragmented platforms now,” Werde explains. “People discover songs, not the stories behind them.”

The Spirit Lives On

Despite it all, Judy Collins sees hope in her audiences.

At 85, she still tours and sings classics like Where Have All the Flowers Gone — and everyone joins in.

“These aren’t just protest songs,” she says. “They’re about life. About what we all face together.”