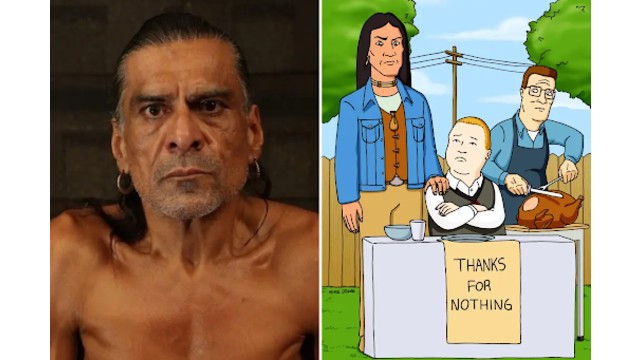

This image released by SRH shows a scene from Hundred of Beavers. (SRH via AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — It might be hard to believe, but Mike Cheslik wasn’t thinking about changing the future of cinema when he was making Hundreds of Beavers. Instead, Cheslik was in the snowy Northwoods of Wisconsin with a small crew of friends, laughing as his co-worker, Ryland Tews, fell over for comedic effect.

"I kept thinking during filming, this would be so ridiculous if it became some kind of legend," Cheslik admits.

Yet, against all expectations, Hundreds of Beavers has achieved a sort of cult status in the film world. Made for just $150,000 and released through self-distribution, the film has carved out a niche in a movie industry often dominated by big-budget blockbusters.

The film is a black-and-white, wordless slapstick comedy featuring a 19th-century applejack salesman (played by Tews) battling an army of beavers, all portrayed by actors in oversized mascot costumes. Though it might not look expensive, the movie’s creativity and quirky charm set it apart from much of Hollywood’s output. With over 1,500 visual effects shots, many created on Cheslik’s home computer, it draws inspiration from old-school slapstick, reminiscent of Buster Keaton and The Naked Gun.

At a time when independent filmmaking is more difficult than ever, Hundreds of Beavers might offer a glimpse into a new way forward, even if that path involves a lot of beaver costumes.

When no major distributor showed interest, the filmmakers chose to take matters into their own hands, launching the film with a traveling roadshow. Since its release in January, the film has played in at least one theater every week, though never in more than 33 theaters at once. (For comparison, blockbuster films typically screen in 4,000 locations.) Over half of the film's $500,000 in ticket sales came after it was made available on video-on-demand.

Daniel Scheinert, co-director of the Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once, has even declared Hundreds of Beavers to be "the future of cinema." While the statement might sound surprising for a movie about a man in a giant beaver hat, it highlights a growing trend in the shrinking movie industry: DIY filmmaking is stepping in to fill the gap left by Hollywood’s cautious, corporate-driven approach.

“I hope people stop making films that look like commercials and start getting back to the basics, letting their imagination run wild,” says Tews, who co-wrote the film with Cheslik. “Hollywood isn’t the gold standard anymore. It’s not all that.”

The North American box office has been struggling this year, with revenues down 11% from last year and 25% from pre-pandemic levels. In 2024, 41 wide releases grossed less than $3 million—nearly three times the number in 2019. The rising costs of making and marketing films are making it harder for indie distributors to take chances. For example, Paramount spent millions promoting Gladiator II by running trailers on over 4,000 platforms. Even big-budget films have a hard time capturing people’s attention.

In this environment, many filmmakers are starting to question whether big budgets are necessary for making meaningful films. Directors like Brady Corbet, whose The Brutalist was made for under $10 million, and Sean Baker, whose Tangerine was shot on iPhones, argue that smaller budgets don’t have to compromise creativity. Baker's $6 million film Anora has earned critical acclaim this year, proving that lower costs don't mean sacrificing quality.

Hundreds of Beavers is a smaller-scale example, but it too demonstrates that independent films can still succeed on the big screen. On December 5, the film will kick off a nationwide encore tour, playing at 70 theaters—a record for the movie. They’re calling it "A Northwoods Christmas."

This victory tour marks a major milestone for Hundreds of Beavers, a low-budget indie hit that has earned its place in the world of cinema. Cheslik hopes the film inspires other filmmakers to embrace the same kind of inventive spirit found in viral TikToks, showing that anyone with a phone and a creative idea can make a full-length feature.

“You can still do whatever you want,” Cheslik says. “No one will stop you if you take a phone and make a 90-minute movie instead of a 30-second clip.”