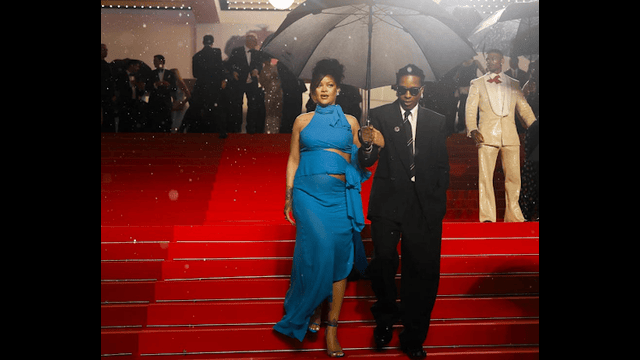

The Romans had a unique way of celebrating and enjoying festive occasions. CNN

Imagine a grand feast with mountains of food: oversized turkeys, holiday hams, pies, cakes, and countless side dishes. While that may sound like an extravagant celebration by today’s standards, it pales in comparison to the indulgence of ancient Roman banquets. These lavish affairs were not just about eating; they were a public display of wealth, power, and social status, stretching long into the night and filled with strange customs and foods.

The Romans considered eating to be one of the highest forms of celebration, reflecting both their civilization and zest for life. “Eating was the supreme act of civilization and celebration of life,” said Alberto Jori, a professor of ancient philosophy at the University of Ferrara in Italy. The upper class would gather in grand dining halls where feasts became more than just a meal—they were performances of luxury.

The Roman menu was a unique blend of sweet and savory flavors, often combined in unexpected ways. Lagane, a short pasta dish made from chickpeas, was transformed into a honey cake with fresh ricotta cheese. The Romans loved garum, a pungent fish sauce that was used in every dish, even as a dessert topping. Garum was made by fermenting fish entrails and blood under the hot Mediterranean sun, resulting in a powerful umami flavor that added depth to their meals.

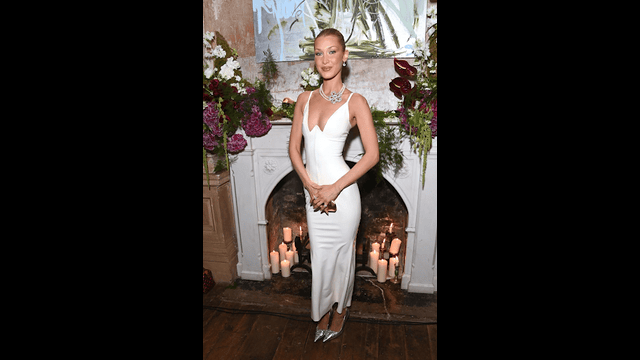

"The Roses of Heliogabalus," a painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema from 1888, depicts Roman guests enjoying a lavish banquet. CNN

The banquets were often filled with exotic dishes like game meats—venison, wild boar, rabbit, and pheasant—alongside seafood such as oysters, shellfish, and lobster. But the Roman hosts went further, serving bizarre delicacies to outdo each other. Parrot tongue stew and stuffed dormouse were regular menu items. Dormice were fattened in pots for months, then sold at markets for these extravagant feasts. “Huge quantities of parrots were killed to have enough tongues to make fricassee,” Jori noted, pointing out the lengths Romans went to for opulence.

Food historian Giorgio Franchetti, who has researched these ancient meals, shared some of the more unusual recipes found in Roman texts. One such dish, invented by Marcus Gavius Apicius, was salsum sine salso—a fish stuffed with cow liver that was meant to surprise and amaze guests. The Romans loved such playful, shocking dishes that doubled as entertainment.

Beyond the eccentric foods, Roman feasts were characterized by bizarre social customs. Guests would often lie down to eat, a symbol of wealth and leisure. They reclined on cushions, eating with their hands while slaves cut up the food for them. During these long affairs, it wasn’t unusual for revelers to vomit between courses in order to make room for more. This practice, referred to as vomitorium, helped keep the indulgence going for hours.

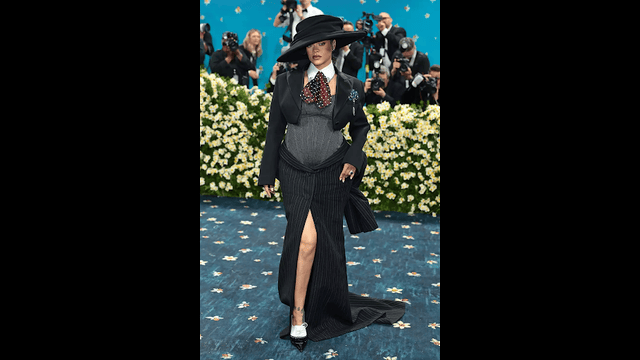

This 2nd-century A.D. mosaic shows a floor covered in food remnants, designed to hide the mess left behind after a banquet. Getty Images

Additionally, bodily functions were not hidden at these banquets. Guests might relieve themselves at the table, with a servant bringing a “piss pot” when needed. It was also customary to let out gas at the table, as the Romans believed that holding in flatulence could lead to death. In fact, Emperor Claudius even issued a decree encouraging guests to pass gas during meals.

For the wealthy, the act of lying down to eat was seen as a luxury reserved only for men. Women either ate separately or sat beside their husbands while he reclined. This practice was considered a display of dominance by men, who held the right to relax while eating, while women had to remain attentive.

Roman banquets were also filled with superstitions. Anything that fell from the table, like bread or wine, was considered a gift from the afterworld and could not be picked up. Guests would avoid retrieving food that fell to the floor for fear of angering the spirits. Spilling salt, for instance, was considered a bad omen.

For the Romans, these lavish feasts were not just about food—they were about showing off their wealth, living life to the fullest, and keeping death at bay. After all, in their eyes, the best way to avoid death was to live as indulgently as possible, savoring every moment. Some, like the epicure Apicius, even went so far as to take their own lives when they could no longer afford such lavish banquets.