Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Jennifer Whiteside, left, arrive for a news conference in Vancouver, B.C., Sunday, Feb. 5, 2023. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

On the same day that the British Columbia government's approach to the overdose crisis experiences a significant shift, the provincial coroner reports another 192 fatalities due to illicit drugs in March. Concurrently, Federal Mental Health and Addictions Minister Ya'ara Saks announces that Health Canada has granted approval for B.C.'s request to once again prohibit the use of illicit drugs in most public areas.

Solicitor General Mike Farnworth, speaking separately at a press conference, attributes the changes to addressing concerns voiced by communities, the public, and law enforcement regarding drug use in public spaces. Farnworth clarifies that decriminalization was never intended to permit drug use in public, stressing that addiction is a health issue rather than a criminal one. He expresses gratitude to Health Canada for the decision, noting that public drug use will no longer be allowed in spaces like hospitals, transit, and parks.

Under the revised regulations, police are empowered to intervene when illegal drug use is observed in public. They may compel individuals to vacate the area, seize drugs if necessary, or make arrests as warranted. Farnworth highlights the provision of comprehensive guidance and training to all law enforcement officers across British Columbia to ensure consistent implementation of these measures.

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside underscores the public's desire for safe communities while also emphasizing the importance of enabling friends and family members to seek assistance without fear of repercussions.

Criticism of the province's decriminalization plan emerges from opposition BC United addictions critic Elenore Sturko, who asserts that it has failed to facilitate access to necessary treatment. Sturko argues that the government is now transferring responsibility to law enforcement, advocating for exploration of alternative models. She contends that the current system has been fundamentally flawed from its inception due to inadequate service provision.

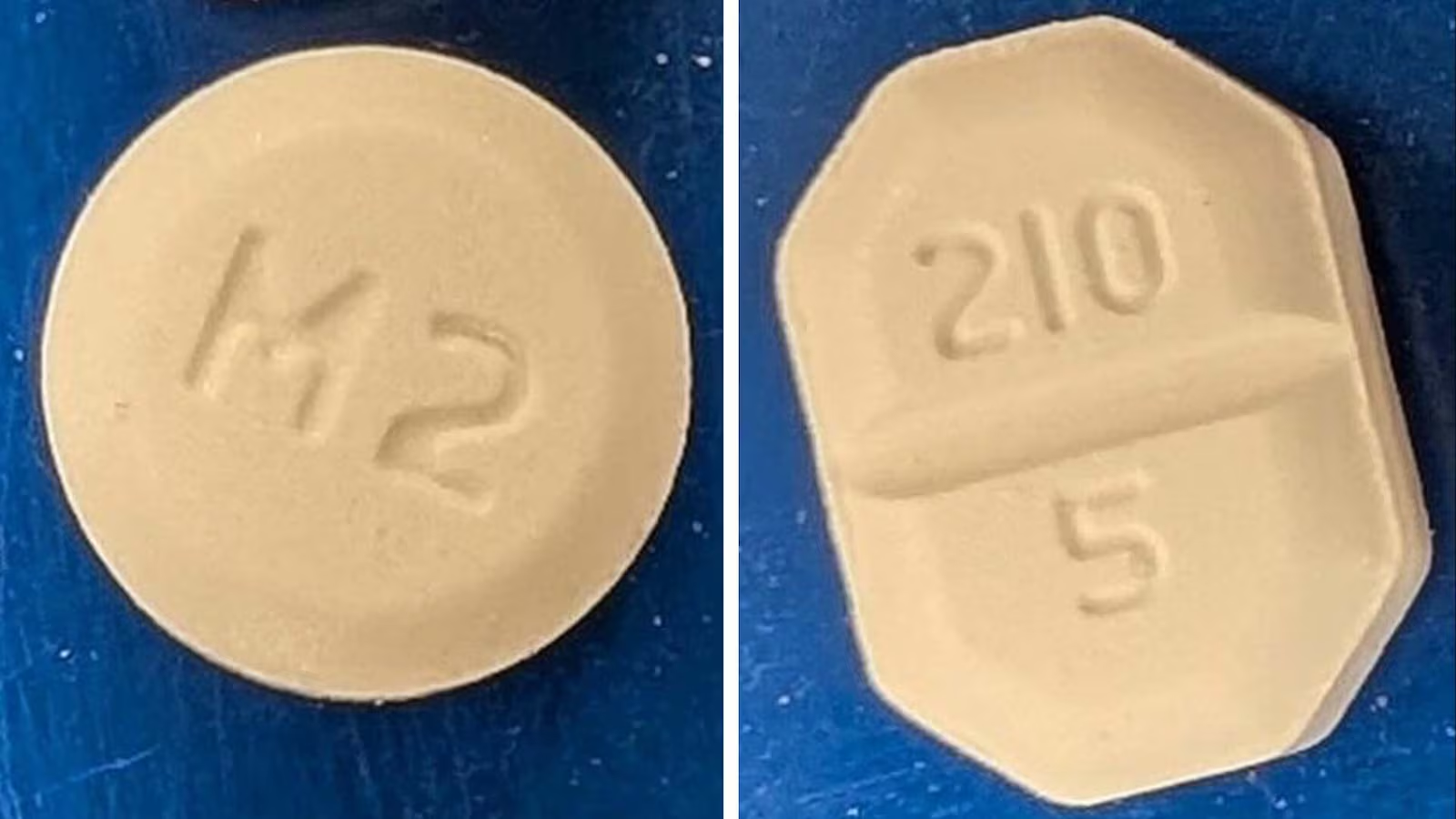

British Columbia has been operating a three-year pilot program, which grants a Criminal Code exemption for personal possession of up to 2.5 grams of drugs like heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamines. Previous attempts by the province to outlaw drug use in public spaces through its own legislation were met with legal challenges. Chief Justice Christopher Hinkson ruled in December that the proposed laws would result in "irreparable harm," prompting the government to seek the Health Canada exception instead of pursuing further legal avenues.

The Harm Reduction Nurses Association expresses deep concern and frustration over Health Canada's decision, asserting that it disproportionately impacts the most vulnerable individuals who are at high risk of fatal drug poisoning. They argue that criminalizing drug use will exacerbate harm and urge the federal government to reconsider its stance.

Since April 2016, at least 14,400 individuals have lost their lives due to drug-related causes in British Columbia. The BC Coroners Service highlights that illicit drugs now rank as the leading cause of death among individuals aged 10 to 59, surpassing accidents, suicides, homicides, and natural causes combined. While there was an 11% decrease in illicit drug deaths in March compared to the same period last year, fentanyl remains prevalent, detected in 85% of unregulated drug-related fatalities.

Whiteside acknowledges the urgency of responding to the ongoing public health emergency, emphasizing the need to reduce barriers and improve access to care. She underscores the importance of ongoing efforts to connect individuals with the necessary support services in a timely manner.