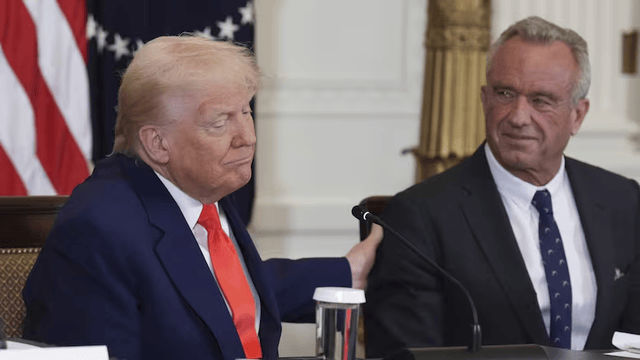

In picture, Dr. Francisco Lopera, right, of the University of Antioquia, a neurologist who spent decades caring for a large Colombian family plagued by early-in-life Alzheimer’s, confers with fellow researcher Yakeel Quiroz. (Massachusetts General Hospital/AP/via The Canadian Press)

Researchers investigating a family with a history of early-onset Alzheimer’s have identified a genetic anomaly that delays the onset of symptoms by five years. This discovery could pave the way for new treatments for the debilitating disease if scientists can understand how a single copy of this rare gene variant provides some protection.

“It opens new avenues,” said neuropsychologist Yakeel Quiroz of Massachusetts General Hospital, who co-led the study published on Wednesday. “There are definitely opportunities to copy or mimic the effects.”

The initial clue of this genetic protection emerged a few years ago. Researchers were examining a large family in Colombia with an inherited form of Alzheimer’s when they found a woman, Aliria Piedrahita de Villegas, who defied her genetic destiny. Despite being predisposed to developing Alzheimer’s in her 40s, she didn’t show mild cognitive issues until her 70s.

The key to her resilience was an extremely rare genetic trait: she had two copies of a mutated gene called APOE3 Christchurch. This unusual gene pair seemed to protect her against the early onset of Alzheimer’s.

Quiroz’s team tested over 1,000 extended family members and identified 27 individuals with one copy of the Christchurch variant. The study, which included researchers from Mass General Brigham and Colombia's University of Antioquia, found that these carriers showed cognitive symptoms at an average age of 52, five years later than their relatives without the variant.

Published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the findings offer hope, according to Dr. Eliezer Masliah of the National Institute on Aging. “It gives you a lot of comfort that modifying one of the copies could be really helpful,” he said, noting that early research is exploring whether certain treatments could induce the protective mutation.

Alzheimer’s affects more than 6 million Americans and an estimated 55 million people globally. Less than 1% of cases are due to inherited genes like those in the Colombian family, which cause early onset. Typically, Alzheimer’s strikes those over 65, with aging being the primary risk factor. The APOE gene, known to influence risk, exists in three main forms. The APOE4 variant increases risk, and having two copies of APOE4 can cause Alzheimer’s in seniors. Conversely, APOE2 reduces risk, while APOE3 is considered neutral.

The Christchurch variant’s protective role was a significant discovery. Silent brain changes, including the accumulation of a sticky protein called amyloid, precede Alzheimer’s symptoms by at least two decades. Amyloid buildup triggers tangles of another protein, tau, which kills brain cells. Previous research suggested that the Christchurch variant might interfere with this tau transition.

Wednesday’s study involved brain scans of two individuals with one Christchurch copy and autopsy analysis of four others. While there is much to learn about how this rare variant affects Alzheimer’s progression, particularly in common old-age cases, Quiroz pointed out that tau and inflammation are key areas of interest.