Dr. Aditi Khandelwal says removing the ban will not affect the safety of the blood supply, but might bring in much-needed blood donations. (Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press)

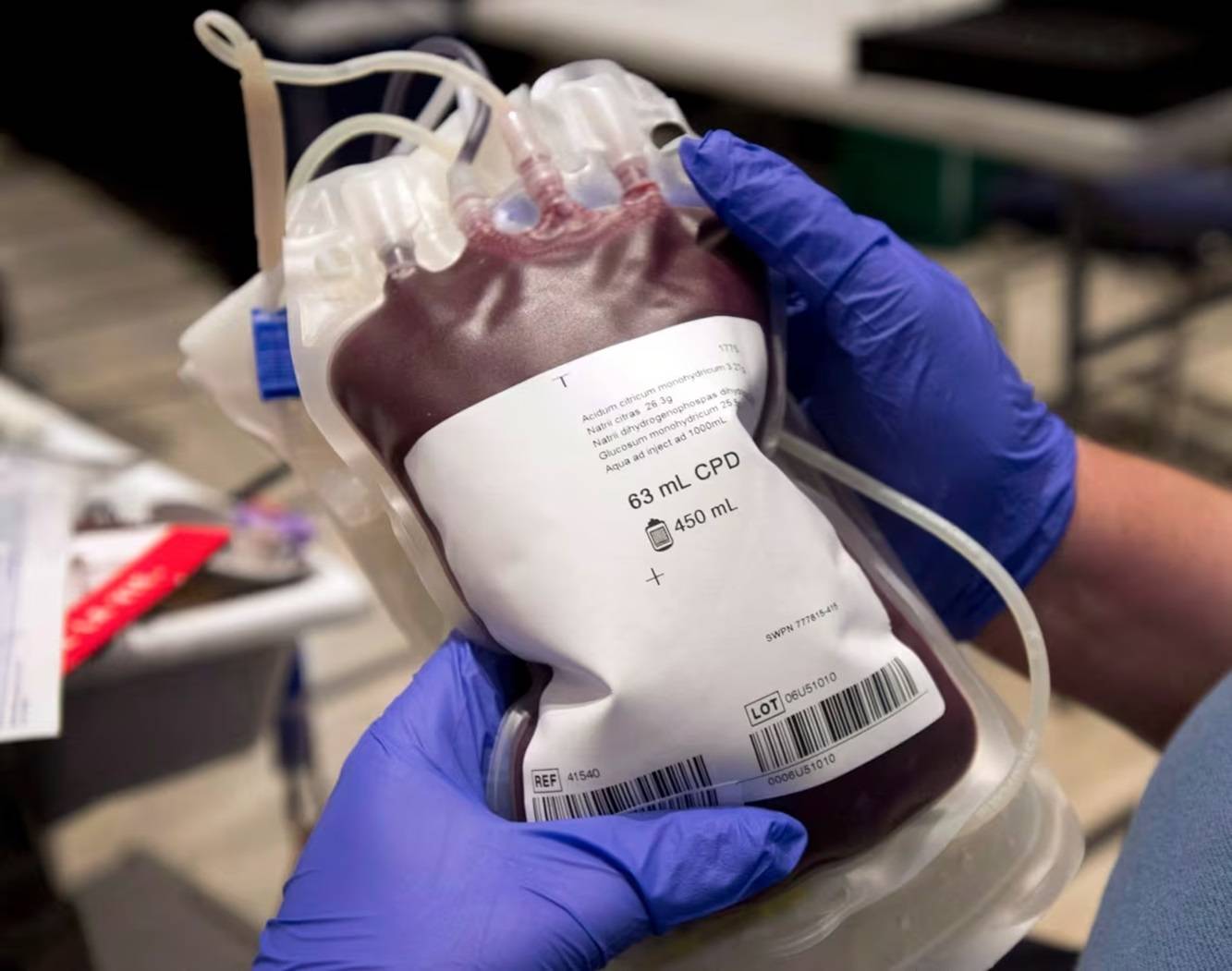

Health Canada has given its approval to lift the long-standing ban on blood donations from individuals who resided or traveled extensively in the United Kingdom, Ireland, or France during the 1980s and 1990s, according to an announcement by Canadian Blood Services on Wednesday.

Implemented over two decades ago by various blood agencies globally, the ban aimed to prevent the transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the human form of "mad cow disease" or bovine spongiform encephalopathy.

After almost 30 years of extensive research and surveillance, it is now evident that individuals previously barred from blood donation due to travel history can do so safely, stated Dr. Aditi Khandelwal, Medical Officer for Canadian Blood Services. The removal of this criterion is not expected to compromise the safety of the blood supply but may expand the pool of potential donors, including those recently deferred for these reasons, she added.

This decision follows similar actions taken by the United States and Australia in 2022, reflecting a collective effort by experts worldwide to address this particular issue.

Héma-Québec, responsible for managing the blood supply in Quebec, received authorization from Health Canada to lift the same ban, aligning with the broader national shift in policy.

Approximately 70,000 people in Canada have been prevented from donating blood since 2003 due to their travel history in the specified regions, according to Ron Vezina, Vice-President of Public Affairs at Canadian Blood Services. In the last five years alone, around 7,500 individuals faced deferral, with the possibility of reconnecting with these potential donors.

The new eligibility criteria, effective December 4, encompass individuals who spent three months or more in the U.K. between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 1996, or received a transfusion there. Similarly, those who spent five years or more in France or the Republic of Ireland between 1980 and 2001, or received a transfusion there, may now be eligible to donate.

The initial assumption was that individuals spending extended periods in these countries were more likely to have consumed beef products from cows affected by bovine spongiform encephalopathy during a time when knowledge about the disease was limited, explained Dr. Khandelwal.

Notably, only two cases of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from consuming cow products have been reported in Canada. Both cases occurred in individuals who had lived in the U.K. or consumed U.K.-imported beef and were documented in 2002 and 2011, respectively.

Given that the average time from exposure to illness development is around eight and a half years, and with the fatal potential within approximately 14 months, those who lived in high-risk countries during the 1980s and 1990s would likely have developed the disease by now, Dr. Khandelwal emphasized. Additionally, the removal or reduction of white blood cells from blood donations before transfusion adds an extra layer of safety.