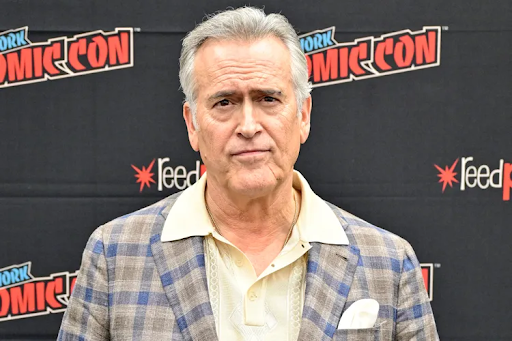

Buffy Sainte-Marie celebrates her Juno for Indigenous Music Album of the Year at the Juno Awards in Vancouver, Sunday, March, 25, 2018. Photo via The Canadian Press

The Juno Awards leadership is taking a cautious approach in deciding whether to revoke Buffy Sainte-Marie’s honors, even after the iconic singer lost her Order of Canada.

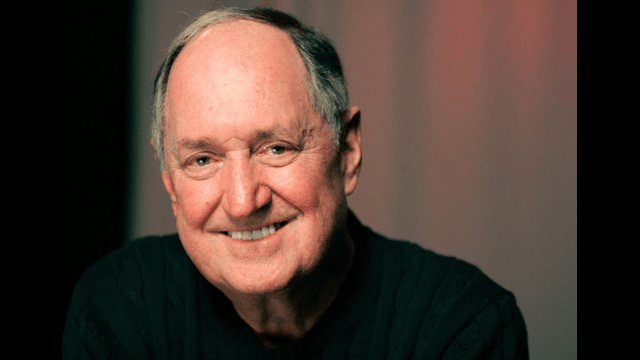

Allan Reid, CEO of the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (CARAS), stated that discussions are ongoing with the Indigenous Music Advisory Committee. However, making a final call remains complex.

“We’ve said from the start that CARAS will make an informed decision, but it must be guided by the Indigenous music community,” Reid told The Canadian Press.

The Junos are one of several Canadian arts organizations re-evaluating past accolades awarded to Sainte-Marie. This scrutiny follows a CBC investigation that questioned her Indigenous identity. The report cited a birth certificate indicating she was born in Massachusetts in 1941. Some of her U.S.-based relatives claimed she was not adopted and has no Indigenous ancestry.

Sainte-Marie has refuted these claims, insisting the CBC report contained errors and omissions. Her management company, Paquin Entertainment, has not responded to inquiries.

Last week, the government officially revoked her Order of Canada. Governor General Mary Simon signed the termination on January 3, marking only the ninth such case in the award’s history. Officials did not comment on specific reasons for the decision.

The revelations have sparked division, especially among Indigenous leaders and artists who once regarded Sainte-Marie as a trailblazer for Indigenous rights. While some continue to support her, others now question her legacy.

Reid acknowledged the differing viewpoints. “We need to ensure we’re aligned with our music community before making a decision,” he said, noting that opinions have evolved over time.

He also emphasized that other organizations have taken months, even years, to reach conclusions. “The Order of Canada process itself took a year. We must have internal discussions before announcing our next steps,” he added, declining to set a timeline.

Several other prestigious institutions are also reassessing Sainte-Marie’s awards. The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards, which honored her in 2010 for lifetime artistic achievement, is consulting with its board. The Polaris Music Prize, which awarded her $50,000 for her 2015 album Power in the Blood, is closely monitoring developments.

The Junos face one of the most intricate decisions, as four of Sainte-Marie’s five wins were in Indigenous categories. She also received the humanitarian award and was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.

Although the Junos website credits her with helping establish the first Indigenous music category, Reid downplayed her role, stating it was a collective effort involving musicians Elaine Bomberry and Shingoose.

In its 54-year history, the Juno Awards have only revoked one award—when pop duo Milli Vanilli lost their international album of the year title in 1990 after it was revealed they did not sing on their tracks.

For now, the fate of Sainte-Marie’s Juno honors remains uncertain, with no rush toward a verdict.