Abraham Fehr and Katarina Wall, Mennonite parents, hold their baby during a vaccination appointment, weeks after the family contracted measles amid an outbreak in Cuauhtemoc, Chihuahua, Mexico, on Thursday, May 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Megan Janetsky)

In a white Nissan, Sandra Aguirre and her team navigate through vast apple orchards and cornfields, making their way to homes in a remote Mennonite community in northern Mexico. Despite their best efforts, many Mennonites are hesitant about the vaccine and often refuse to open their doors. However, some people will listen, ask questions, and a few may even agree to get vaccinated.

Aguirre's daily routine is part of Mexico's broader efforts to combat one of the largest measles outbreaks in decades, which is affecting not only Mexico but also spreading to the U.S. and Canada. The epidemic has been particularly severe in the Mennonite community in Chihuahua, a region where skepticism towards vaccines and government authorities is widespread.

While vaccination campaigns have led to tens of thousands of shots being administered, infections have spread beyond the Mennonite community, reaching Indigenous groups and others. The official count in Chihuahua has reached 922 cases and one death, but health workers believe the true numbers are likely higher due to misinformation and mistrust.

The Mennonite settlement in Cuauhtemoc spans 25 miles and is home to around 23,000 people. The community is largely self-sufficient and tends to avoid outside interference. Many Mennonites rely on social media or anti-vaccine websites for information, while others hear false claims from relatives in the United States.

With its location on the border, Chihuahua is at risk of the disease spreading internationally, making the situation more urgent. As the disease spreads, health officials are facing significant challenges in convincing people to get vaccinated, especially given that the vaccination rate in Mexico has dropped to 76%, well below the 95% required to prevent outbreaks.

This current outbreak began in March, tracing back to an 8-year-old unvaccinated Mennonite boy who travelled to Texas, where a similar outbreak occurred. From there, the virus spread rapidly through the Mennonite community in Chihuahua, moving from schools and churches to workers in local orchards and cheese plants.

Indigenous people like Gloria Elizabeth Vega, who contracted measles despite being vaccinated, have also been affected. Vega was forced to take unpaid leave from her job at a cheese factory, highlighting the broader financial impacts of the outbreak.

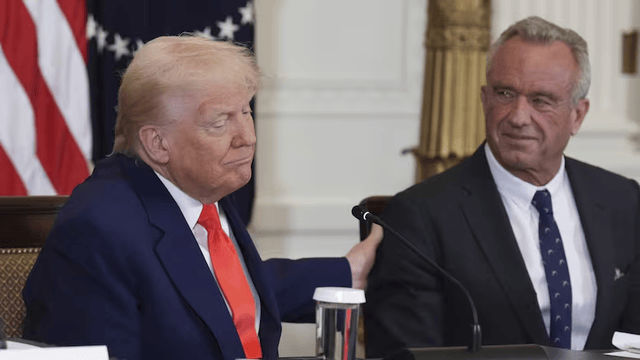

Misinformation surrounding vaccines is a significant issue. Many Mennonites have been exposed to anti-vaccine messages, especially from figures like U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whose views are widely circulated in the community. For some Mennonites, refusing the vaccine is seen as a matter of personal freedom.

Health officials in Chihuahua have been working closely with local Mennonite leaders, who have translated vaccine information into the community's native language, Low German. These leaders are also involved in encouraging vaccination and helping families access health services.

While vaccination efforts have made progress, there remains a portion of the population that is resistant. Health officials are especially concerned for vulnerable groups, such as Indigenous people, who may have limited resources to cope with the outbreak.

For individuals like Vega, the consequences of the outbreak are more than just health-related; it also affects their livelihoods. As a single mother living paycheck to paycheck, Vega struggles to cover basic expenses after her pay was docked during her forced leave.