This illustration shows a person carving an osteoderm from a giant sloth in Brazil around 25,000 to 27,000 years ago, as depicted by researchers. AP Photo

Prehistoric sloths weren’t always the slow-moving tree dwellers we know today. In fact, their ancient ancestors were massive creatures, weighing up to four tons, and equipped with enormous claws. For a long time, scientists believed that humans arriving in the Americas swiftly wiped out these giant ground sloths, along with other massive creatures like mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and dire wolves, through hunting.

However, recent discoveries are challenging this long-held belief, suggesting that humans may have arrived in the Americas much earlier than once thought, and that they coexisted with these giant creatures for thousands of years. This new evidence points to a more complex relationship between early humans and megafauna.

Daniel Odess, an archaeologist at White Sands National Park in New Mexico, said, “There was this idea that humans arrived and killed everything off very quickly — what’s called ‘Pleistocene overkill.’ But new discoveries suggest that humans existed alongside these animals for at least 10,000 years, without making them go extinct.” This finding dramatically alters our understanding of prehistoric life in the Americas.

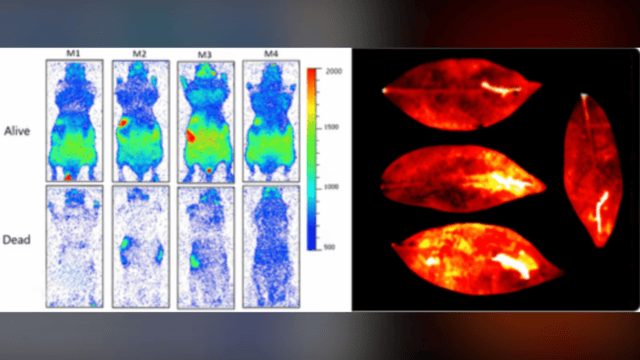

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence comes from a site in central Brazil called Santa Elina. There, researchers discovered bones of giant ground sloths showing signs of manipulation by humans. These sloths once roamed from Alaska to Argentina, and some species had bony plates on their backs, similar to modern armadillos. These osteoderms, it seems, were used by ancient people to make jewelry and other adornments.

At the University of Sao Paulo, researcher Mírian Pacheco examined a sloth fossil, noting that its surface was unusually smooth with a tiny hole near the edge. “We believe it was intentionally altered and used by ancient people as jewelry or adornment,” she said. Other bones from the site are visibly different from unworked osteoderms, suggesting they were carefully crafted by humans.

These artifacts from Santa Elina are estimated to be around 27,000 years old, far older than previously believed for human presence in the Americas. Pacheco’s research indicates that the bones were worked soon after the sloths died, not thousands of years later. This evidence challenges the traditional timeline that suggested humans arrived much later, around 13,000 years ago.

On July 11, 2024, Thais Pansani and Kay Behrensmeyer examined a giant sloth rib bone from central Brazil at the Smithsonian's National Taphonomy Reference Collection in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo)

Pacheco, who grew up learning about the “Clovis First” theory — which stated that the Clovis people were the first to arrive in the Americas around 13,000 years ago — has found new evidence that could upend this story. “What I learned in school was that Clovis was first,” she said, but now, new research methods and techniques are revealing earlier human activities in the Americas.

In recent decades, advancements in DNA analysis and lab technology have provided new insights into human migration and the extinction of megafauna. Although evidence of human presence in the Americas more than 15,000 years ago is still controversial, researchers are uncovering more and more proof from older sites, such as Monte Verde in Chile, which shows human activity 14,500 years ago, and Arroyo del Vizcaíno in Uruguay, where researchers have found signs of human-made marks on bones dating to around 30,000 years ago.

Further evidence of human interaction with megafauna comes from White Sands National Park, where footprints of humans and giant mammals, including sloths, have been discovered and dated to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. Some researchers are still puzzled by the lack of stone tools at these sites, but the footprints themselves remain a powerful piece of evidence.

The ongoing debate about the timing of human arrival in the Americas may never be fully resolved. However, the discoveries at Santa Elina and other sites indicate that humans coexisted with giant sloths and other megafauna far earlier than previously thought — and their impact on the environment was likely more gradual than once believed.