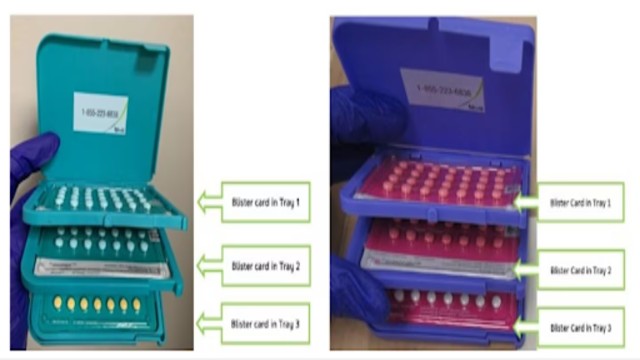

A view of Mpox test kits is displayed in Moldiag, a biotechnology startup in Tamesna, Morocco, Nov 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Mosa’ab Elshamy)

TAMESNA, Morocco (AP) — During the COVID-19 pandemic, African countries faced difficulties in obtaining crucial testing kits, prompting officials to pledge greater independence from imported medical supplies. Now, for the first time, a Moroccan company is fulfilling orders for mpox tests as the virus continues to spread.

Moldiag, a Moroccan startup, began developing mpox tests after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the virus a global health emergency in August. This year, Africa’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) reported over 59,000 mpox cases and 1,164 deaths across 20 countries.

In response to criticism over its slow vaccine rollout, the WHO has announced plans to provide mpox tests, vaccines, and treatments to vulnerable populations in the world’s poorest countries. It has urged the testing of all suspected mpox cases.

However, in some of the most remote areas affected by the outbreak, tests must be sent to distant laboratories for processing. Many provinces in Congo, for example, lack such facilities, and some regions have no access to tests at all. In South Kivu province in eastern Congo, doctors are still diagnosing cases based on visible symptoms and body temperature, making it difficult to track the virus's spread.

"This is a major problem," said Musole Robert, medical director of the Kavumu Referral Hospital in eastern Congo, one of the few treating mpox patients in the area. "The main issue remains the laboratory, which is not adequately equipped."

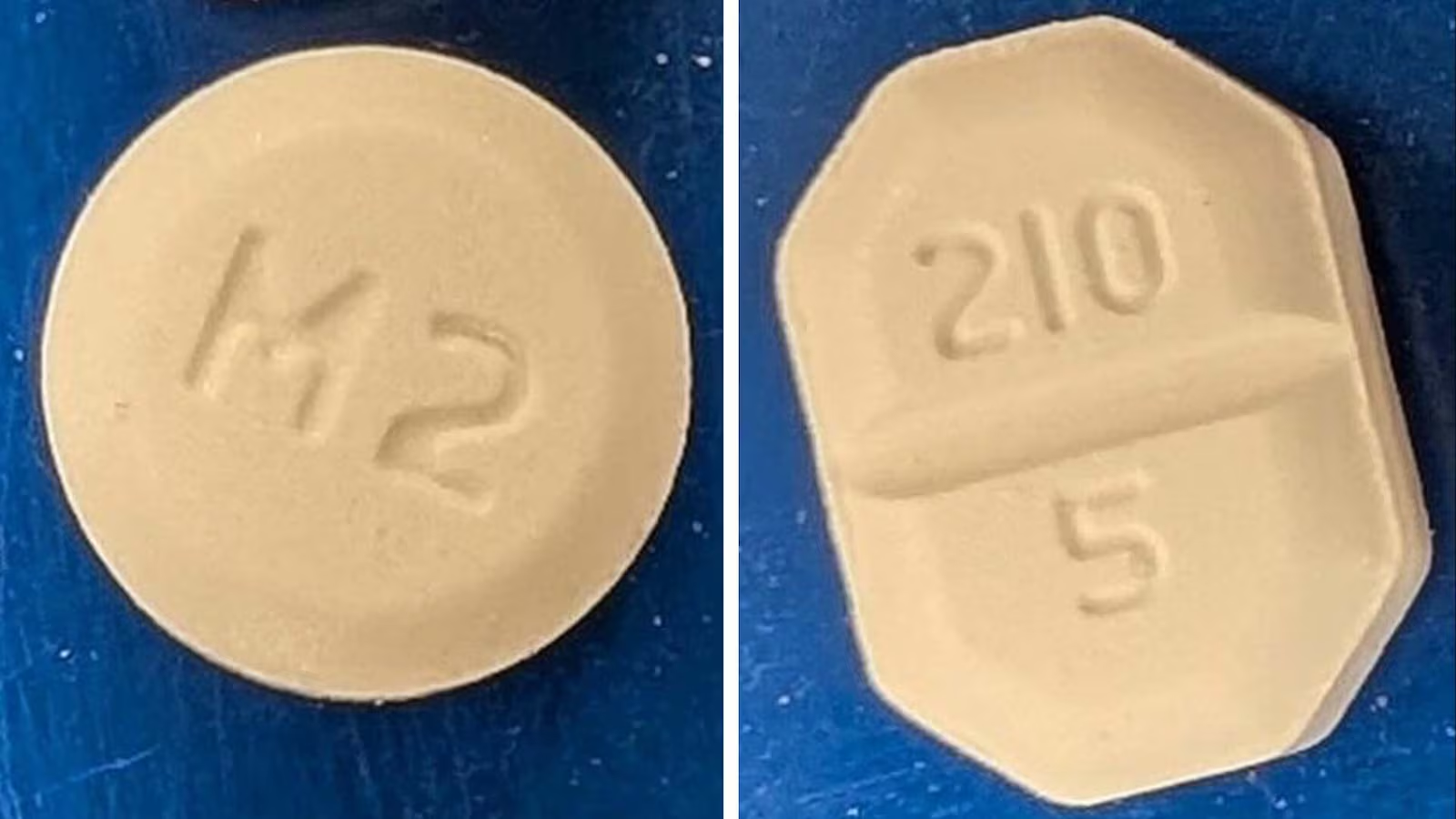

Mpox spreads primarily through close contact with an infected person or contaminated items like clothing and bedsheets. It causes visible skin lesions, and testing is essential because the symptoms can resemble those of other diseases, such as chickenpox or measles.

Employees working in Moldiag, a biotechnology startup in Tamesna, Morocco, Nov 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Mosa’ab Elshamy)

When mpox cases were detected in Western countries, including the United States, in 2022, some companies developed rapid test kits that didn’t require lab processing. However, these efforts were put on hold as the virus appeared to be contained. As outbreaks resurfaced in Africa, scientists grew concerned about the emergence of a more transmissible strain.

Morocco has reported three mpox cases, but the majority of cases have been in central Africa.

Abdeladim Moumen, the founder and chief scientific officer of Moldiag, said that the company’s mpox tests, priced at $5 each, offer an affordable solution to the shortage of testing supplies. In the past month, Moldiag has begun filling orders from countries including Burundi, Uganda, and Congo, as well as Senegal and Nigeria.

"It’s rather easy to send tests from an African nation to another one, rather than waiting for tests to come in from China or Europe," Moumen explained.

Founded within Morocco’s Foundation for Advanced Science, Innovation and Research, Moldiag previously developed similar genetic tests for COVID-19 and tuberculosis. The company received approval from the Africa CDC to distribute its mpox tests in November, though it has yet to seek expedited approval from the WHO, which has approved three mpox tests and is evaluating five others, all produced in North America, Europe, or Asia.

Yenew Tebeje, acting director for laboratory diagnostics at the Africa CDC, said the organization had set up a process to speed up the approval of tests like Moldiag’s, noting that the WHO’s lengthy approval process can delay access to essential diagnostics.

Historically, global health institutions have been slow to ensure the timely availability of medical supplies, such as tests, in Africa, Tebeje added.

To date, only mpox tests that require laboratory processing have been approved by the WHO and Africa CDC. However, there is a growing need for rapid tests that do not require lab processing, and companies like Moldiag are working to develop such tests and secure approval.

Moldiag’s $5 price for its tests aligns with the WHO’s product standards and the demands of health advocates who have criticized the high costs of other tests. Last month, the nonprofit Public Citizen called on Cepheid, one of the WHO-approved manufacturers, to reduce the price of its tests from $20 to $5, citing an analysis by Doctors Without Borders showing that genetic tests could be produced for a fraction of the cost.

The push for African-based production of medical supplies is part of a broader effort by African leaders to address the disparities in access to health resources, which were starkly revealed during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, African leaders called for more localized production of medical supplies to better meet the needs of the continent's over 1.4 billion people, who face a high frequency of public health emergencies.

Moumen emphasized that it makes more sense for tests to be produced closer to where outbreaks are occurring, allowing manufacturers to adapt their products to local needs.

"Experts are starting to realize that Africa needs its own tests for Africa," he said.