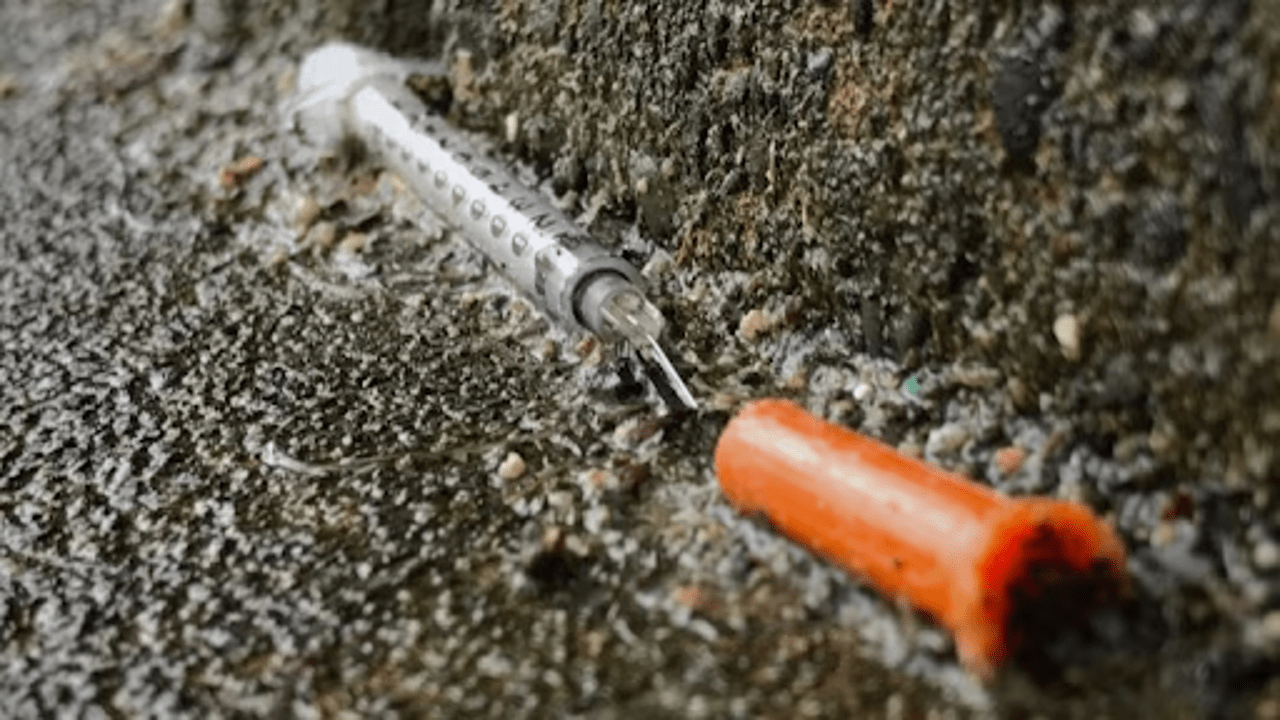

Over the past four years, Canada has faced a devastating drug crisis, leading to over 30,000 deaths. The idea of mandating addiction treatment is becoming more popular among policymakers, though its actual success remains uncertain. (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

The ongoing drug crisis in Canada has resulted in thousands of deaths annually, sparking debates over whether involuntary drug treatment should be implemented. This approach, though divisive, is gaining support from some political leaders who see it as a potential way to address the alarming increase in opioid-related deaths. However, experts highlight that evidence of its effectiveness remains inconclusive.

In recent years, involuntary treatment proposals have been put forth across Canada, despite a 2023 review by the Canadian Society of Addiction Medicine showing mixed outcomes. This review, which analyzed 42 studies worldwide, found that while some instances showed slight benefits in retaining patients in treatment, few reported long-term decreases in substance use. Most studies either found no significant difference or negative outcomes when comparing forced and voluntary treatments. The report ultimately concluded that more research is needed to guide policy decisions.

Dr. Anita Srivastava, an addiction medicine expert in Toronto, argues that the push for involuntary treatment may be more about appeasing public frustration than finding a genuine solution. “It’s a response to the visible pain and suffering, a way to avoid confronting the root issue,” she said. Meanwhile, Keith Humphreys, a psychiatry professor at Stanford University and adviser to Alberta’s addiction recovery panel, supports involuntary treatment as an emergency measure in some cases. He emphasized that addiction is a chronic condition, often preventing individuals from seeking help on their own.

The political momentum for forced treatment is especially evident in Alberta. Premier Danielle Smith's government has pledged to introduce legislation that would authorize forced treatment. The province has also expanded its voluntary treatment services, adding thousands of new detox and recovery spaces since 2019.

Critics argue that the core issue lies in the limited availability and accessibility of voluntary treatment. Dr. Katie Dorman, who has worked extensively in addiction care in Toronto, described the current situation as paradoxical. "It's unreasonable to talk about forced treatment when so many willing patients face barriers to access," she said. In Ontario, the wait time for a spot in an intensive residential program can extend to nearly three months. Alberta’s wait times are somewhat shorter, but the demand still outpaces availability.

Advocates for forced treatment, like Marshall Smith, former chief of staff in Alberta, see it as a last-resort lifeline. Drawing on his personal experience overcoming a methamphetamine addiction after facing an ultimatum—jail or treatment—Smith believes that forced treatment, although not ideal, can be better than allowing people to continue using drugs with the risk of death looming.

However, opponents maintain that without enough resources for voluntary programs, any move towards compulsory treatment will remain controversial. Dan Werb, who leads the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation, stressed that existing evidence does not strongly support the effectiveness of forced treatment. He urges policymakers to prioritize funding voluntary services to help those who already seek assistance but struggle with access.