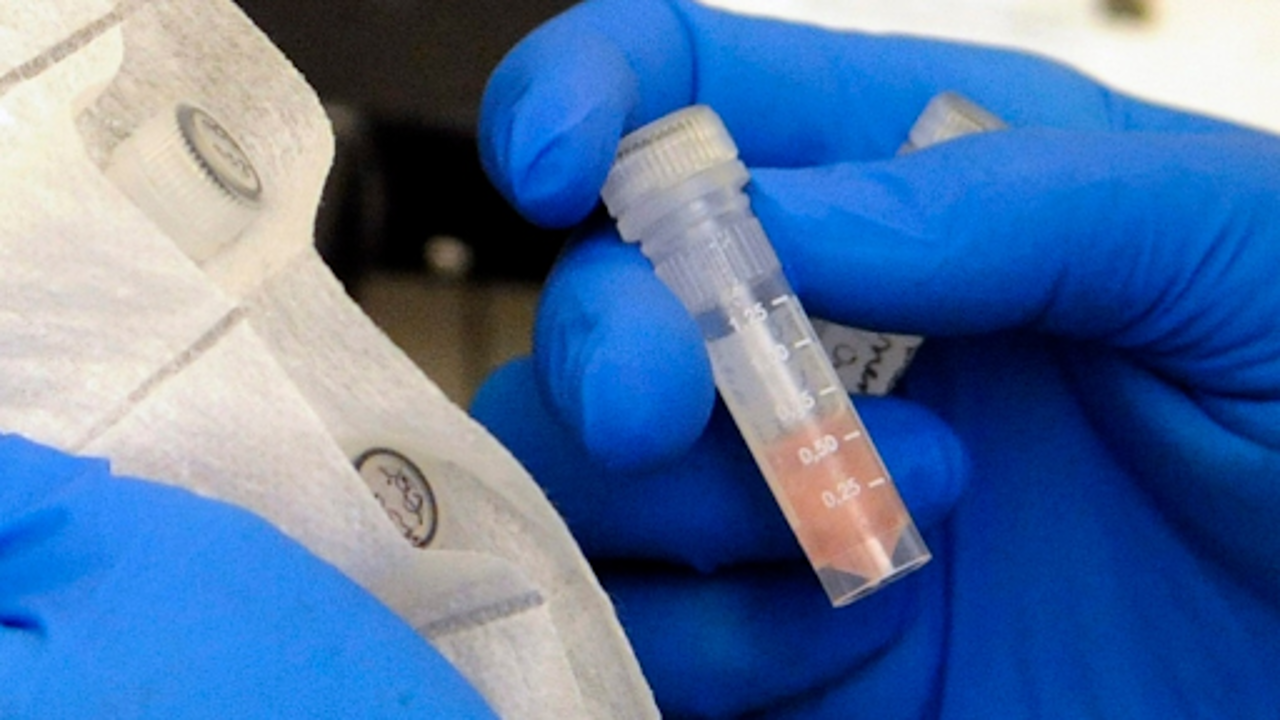

Laboratory technician packages cerebrospinal fluid. Current meningitis tests can take days to process while the infection could be fatal within hours.(AP Photo/Hannah Foslien)

A rare bacterial infection potentially leading to meningitis is increasing in some Canadian provinces, yet an infectious diseases specialist assures it won’t “spiral out of control.”

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is caused by bacteria that can trigger severe inflammation in the brain and spinal cord, posing a potential fatality risk.

As of this year, Ontario and Manitoba have recorded cases, with Toronto Public Health confirming 13 cases in 2024, marking the highest tally since 2002, as per a spokesperson from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Preliminary data from the National Microbiology Laboratory suggests the national IMD case count hasn’t risen compared to previous years, averaging nearly 115 cases annually from 2010 to 2021.

Should there be concern? “It shouldn’t spiral out of control. We have a robust vaccination program in Canada, emphasizing the importance of broader vaccinations in areas with high human interaction,” stated infectious diseases specialist Dr. Dale Kalina in a CTV News Channel interview.

The virus spreads through airborne droplets, such as sneezing and close talking, making larger gatherings and dormitories susceptible to outbreaks, noted Kalina. Serious cases can lead to sepsis, bloodstream infections, amputations, and death. Initial symptoms include fever, nausea, headache, stiff neck, confusion, and light sensitivity.

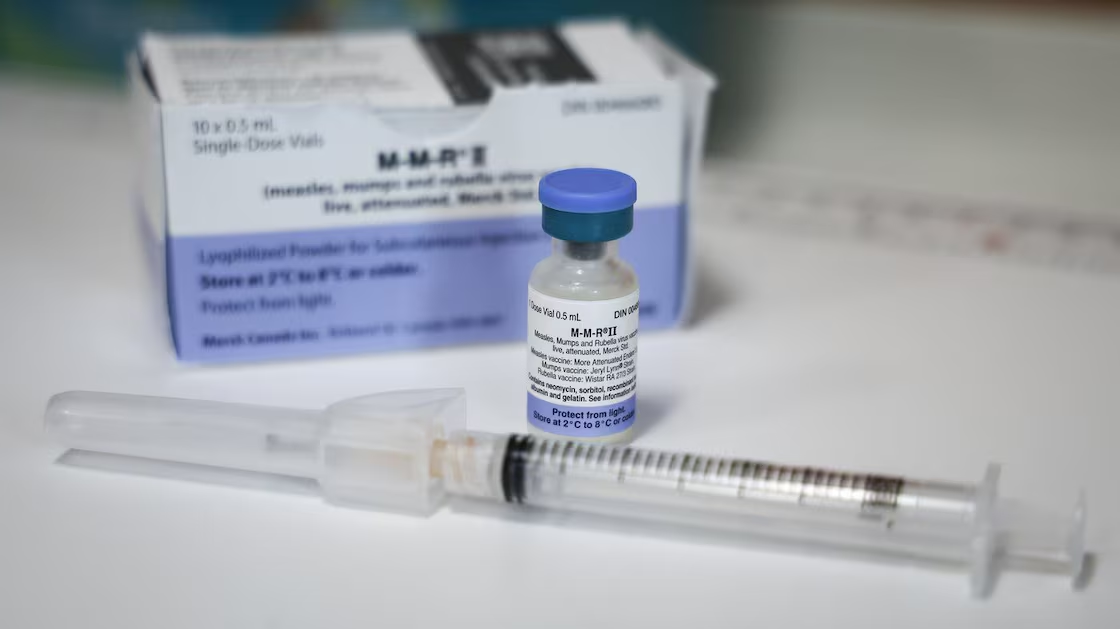

How can I protect myself? Kalina highlighted multiple meningococcus strains and available immunizations against most, typically administered to children around 12 months and during adolescence, with vaccination schedules varying by province and extended to immunocompromised individuals.

Post-exposure antibiotics are recommended to prevent bacterial infection development following IMD exposure, regardless of vaccination status, particularly for close contacts like household members or child care attendees with a case of IMD, as mandated by the federal government.

Although invasive meningococcal disease primarily affects children under five, unvaccinated teens and young adults are also at risk. PHAC notes peak cases during winter and spring, affecting approximately one in 100,000 Canadians.

"Many people may not realize they’ve contracted IMD, but public health officials actively reach out to close contacts," emphasized Kalina.

PHAC monitors IMD closely, collaborating with public health partners to ensure nationwide health and safety.

"Individuals displaying IMD symptoms should seek immediate medical assistance," advised an agency spokesperson via email.