Minister of Indigenous Services Patty Hajdu rises during Question Period in the House of Commons on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Thursday, June 13, 2024. A First Nation in northern Manitoba says its nursing station is operating at half-capacity, and as a result members are going without the care they need. THE CANADIAN PRESS/ Patrick Doyle

OTTAWA - The chief of a northern Manitoba First Nation reports that their nursing station is operating at half-capacity, leaving many members without necessary care.

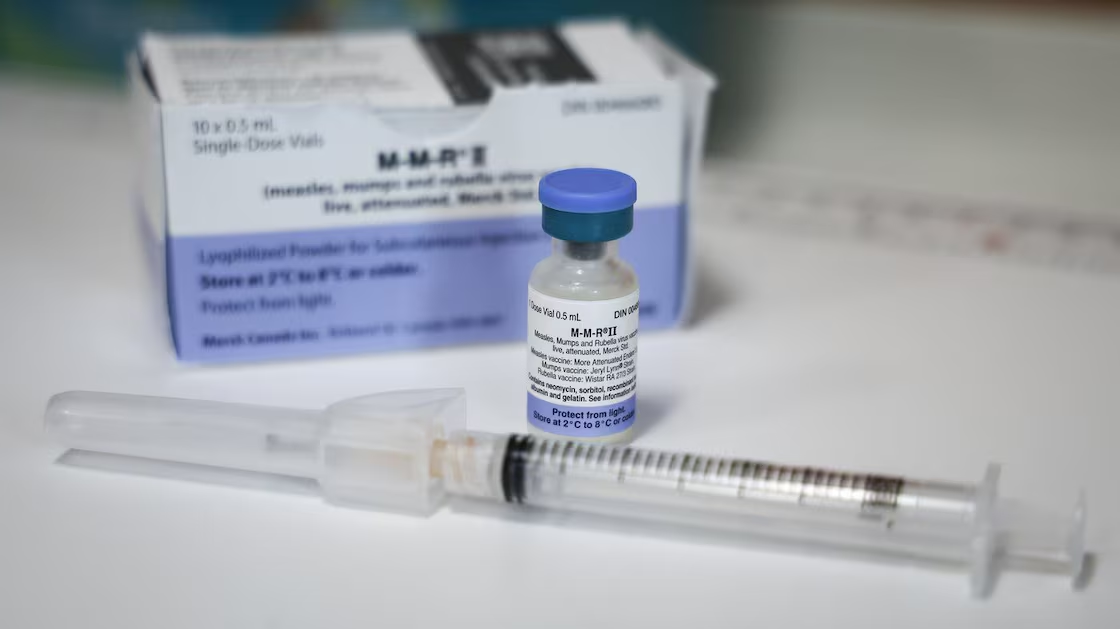

Chief David Monias of Pimicikamak Cree Nation stressed that health care is supposed to be universal, comprehensive, accessible, affordable, and properly funded, but none of these principles are being met in his community. Ideally, the community should have 13 to 14 nurses, but most days only five or six are available. Due to this shortage, the nurses are primarily handling emergencies, leaving patients with chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension without routine care. Consequently, when conditions worsen, patients are often flown to Winnipeg for treatment, as the local station can't manage acute issues. Earlier this year, the situation worsened to the point where a state of emergency was declared.

Monias highlighted severe cases where individuals with undiagnosed brain tumors only discovered their conditions after being sent to Winnipeg. The federal government hires nurses for the First Nation, but their roles are transferable to multiple communities, leading to instability. Some nurses have quit due to burnout from overwork. Government data shows a 67 percent operational vacancy at nursing stations in remote Manitoba First Nations communities last fiscal year, with similar issues in Ontario.

The 2023-24 fiscal year saw all Indigenous Services Canada-operated nursing stations in Manitoba running at reduced capacity due to staffing shortages. Indigenous Services employs nurses in 50 remote or isolated nursing stations across Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. To avoid closures and maintain emergency services in Manitoba, the region has had to triage and relocate various healthcare professionals.

Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu acknowledged the nationwide nursing shortage and stated the department's efforts to increase applicants for remote communities. The goal is to balance immediate staffing needs while building long-term capacity within First Nations communities to ensure a stable workforce.

Monias expressed interest in his community taking control of the nursing station but is wary of inheriting a broken system. He suggested that local hiring authority would allow them to retain staff who wouldn't be transferred elsewhere. However, he noted that accepting responsibility for healthcare would be challenging due to the system's complexity.

The federal government recently posted job listings for nurses in remote First Nations communities in Manitoba, Alberta, and Ontario. In Manitoba, nurses will be flown from St. Andrews to various First Nations on a rotational basis. They can receive up to $6,750 as a recruitment allowance after the first month and up to $16,500 as a retention allowance in the second year, in addition to their base salary.

Minister Hajdu emphasized that while the department is doing its best, the ultimate solution lies in building local capacity within First Nations to hire nurses from their own communities. This approach would create a stronger labor pool, reducing the need to attract external nurses to remote areas.