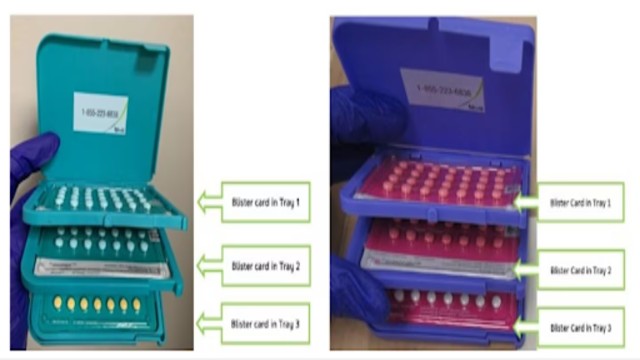

A injection kit is seen inside the Fraser Health supervised consumption site in Surrey, B.C. Tuesday, June 6, 2017. Doctors on Vancouver Island say they're establishing overdose prevention sites on the grounds of hospitals because the B.C. government hasn't lived up to its pledge to set aside space as promised. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward

Efforts by physicians and volunteers to create overdose prevention sites at hospitals in Nanaimo and Victoria were halted on Monday after Island Health, the regional health authority, shut them down. Volunteers subsequently relocated their operations across the street.

The initiative, driven by frustration with the B.C. government’s unfulfilled promise to establish such sites at hospitals, was spearheaded by a group of doctors and healthcare professionals. Dr. Jess Wilder, an addictions and family medicine specialist in Nanaimo, described the sites as critical for saving lives amidst the ongoing toxic drug crisis.

However, when volunteers attempted to set up a site on the grounds of Nanaimo General Hospital, they were confronted by police and hospital security. According to Wilder, organizers were told they would face arrest for trespassing if they proceeded. The group then moved their services off hospital property to a nearby location.

Dr. Réka Gustafson, Island Health’s chief medical health officer, defended the authority’s actions in a statement, emphasizing the importance of safety for everyone on hospital grounds. She stated that unapproved clinical services or demonstrations could not be permitted on hospital property. Gustafson also noted Island Health’s focus on improving access to care during the toxic drug crisis but did not elaborate on specific measures.

Wilder criticized the government for its inaction, recalling a provincial commitment in April to open overdose prevention sites at all hospitals. She and her colleagues have since been using their personal resources to set up temporary “pop-up” sites to address the crisis. Wilder lamented the preventable deaths caused by drug overdoses and expressed frustration with the politicization of harm reduction efforts.

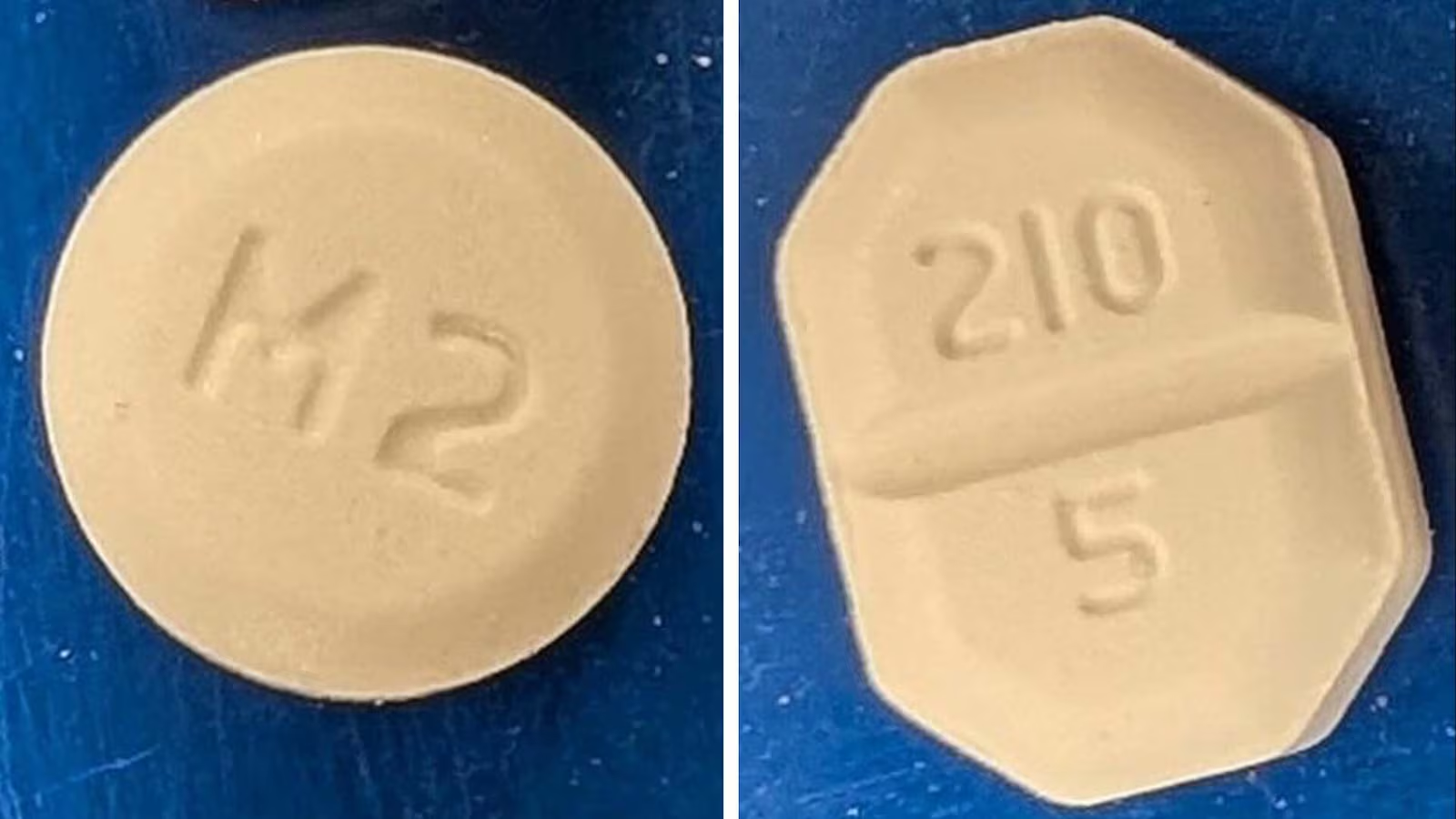

Citing an example of interference, Wilder described how a harm-reduction vending machine at a hospital was removed following public opposition from a political candidate. “The fact that a social media post from someone without medical expertise can outweigh years of advocacy and medical evidence is deeply disheartening,” she said.

Dr. Ryan Herriot, an addictions and family medicine practitioner in Victoria, highlighted the urgency of their actions. The group set up their prevention sites on a day when welfare recipients receive checks—a period often linked to increased overdose fatalities. Herriot described it as “the most lethal day of the month” for many drug users.

The physicians belong to a group called Doctors for Safer Drug Policy, which aims to amplify expert voices in harm reduction and drug policy discussions. Herriot acknowledged that professionals have been too hesitant to engage publicly, leaving room for misinformation to dominate the narrative. “We need to step out of our clinical roles and make our voices heard,” he said.

Both Wilder and Herriot underscored the moral distress faced by healthcare providers witnessing preventable deaths. They, along with other volunteers, plan to continue running the relocated prevention sites throughout the week.