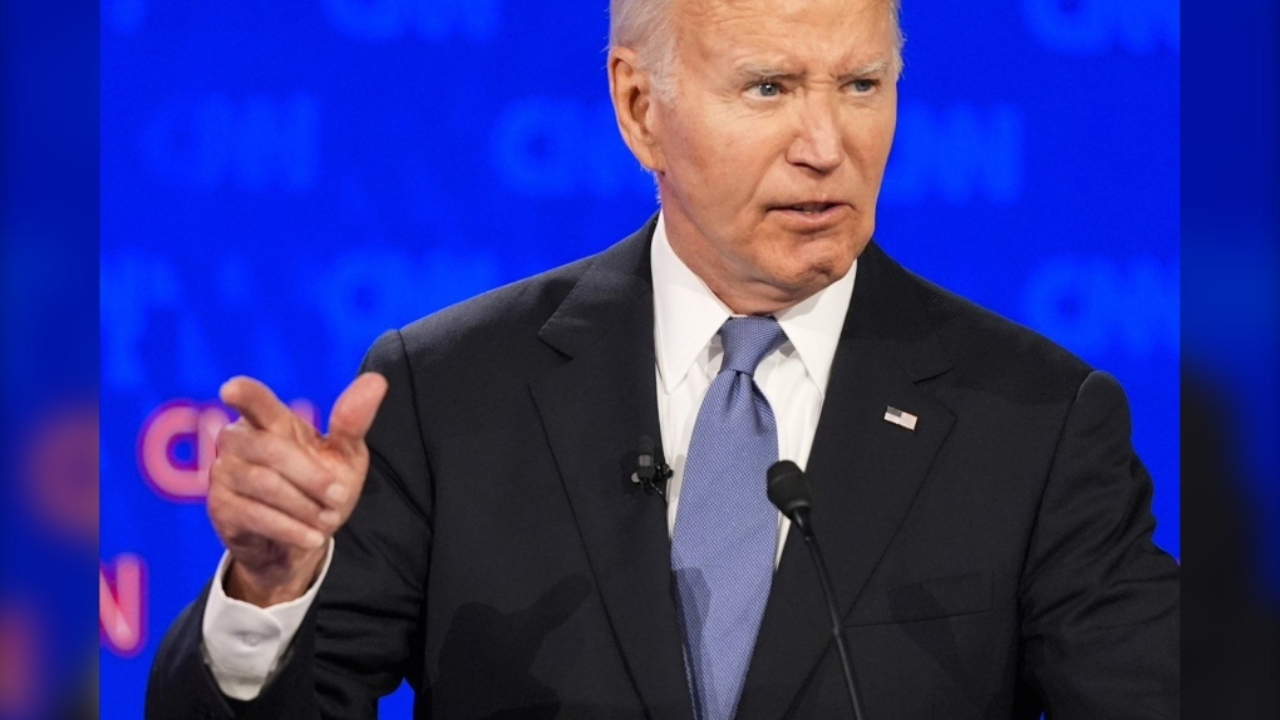

Joe Biden, the President of the United States, talks at a presidential debate on CNN alongside former President Donald Trump, the Republican presidential candidate, held on June 27, 2024, in Atlanta.

In the realm of politics, calls for cognitive tests have become a new norm, especially in Washington. After a lackluster debate performance, U.S. President Joe Biden faced demands for such tests, despite his physician confirming regular neurologic exams with passing results.

Former President Donald Trump, not far behind in age, sparked his own controversy by boasting about acing a cognitive test in 2018, while also misidentifying the administering doctor.

Amidst the scrutiny, what exactly can cognitive tests unveil about brain health, and where do their limits lie? And beyond presidents, do everyday older adults benefit from these assessments?

Cognitive tests serve as brief screenings, typically lasting about 10 minutes, designed to evaluate various brain functions. Common assessments include the MMSE (Mini-Mental State Exam) and the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment).

Tasks range from recalling lists of words to performing arithmetic calculations under time pressure, assessing memory, attention, and spatial awareness.

These tests don't diagnose specific health conditions but serve as indicators for further investigation. Scores may not always reflect underlying cognitive decline, especially in highly educated individuals adept at test-taking. Therefore, additional tests might be necessary based on observed day-to-day concerns.

Galvin emphasizes that these screenings offer a snapshot in time and don't capture a person's overall functional status. However, reporting any concerns prompts primary care doctors to administer these tests, particularly during Medicare wellness visits for seniors aged 65 and older.

Annual screenings can detect subtle changes, akin to monitoring blood pressure to catch deviations from the norm.

Cognitive screenings, conducted by primary care providers, focus on pencil-and-paper assessments. In contrast, neurologic exams, overseen by specialists, involve comprehensive physical evaluations. These exams scrutinize speech patterns, reflexes, and muscle function to detect signs of neurological disorders.

While aging naturally slows cognitive processes, it doesn't equate to cognitive impairment. Slower recall or temporary memory lapses are common with age but don't necessarily indicate disease.

Certain reversible conditions like infections or medication side effects can mimic cognitive decline. Addressing these underlying issues requires consultation with specialists who may recommend neuropsychological testing or brain scans to pinpoint specific conditions.