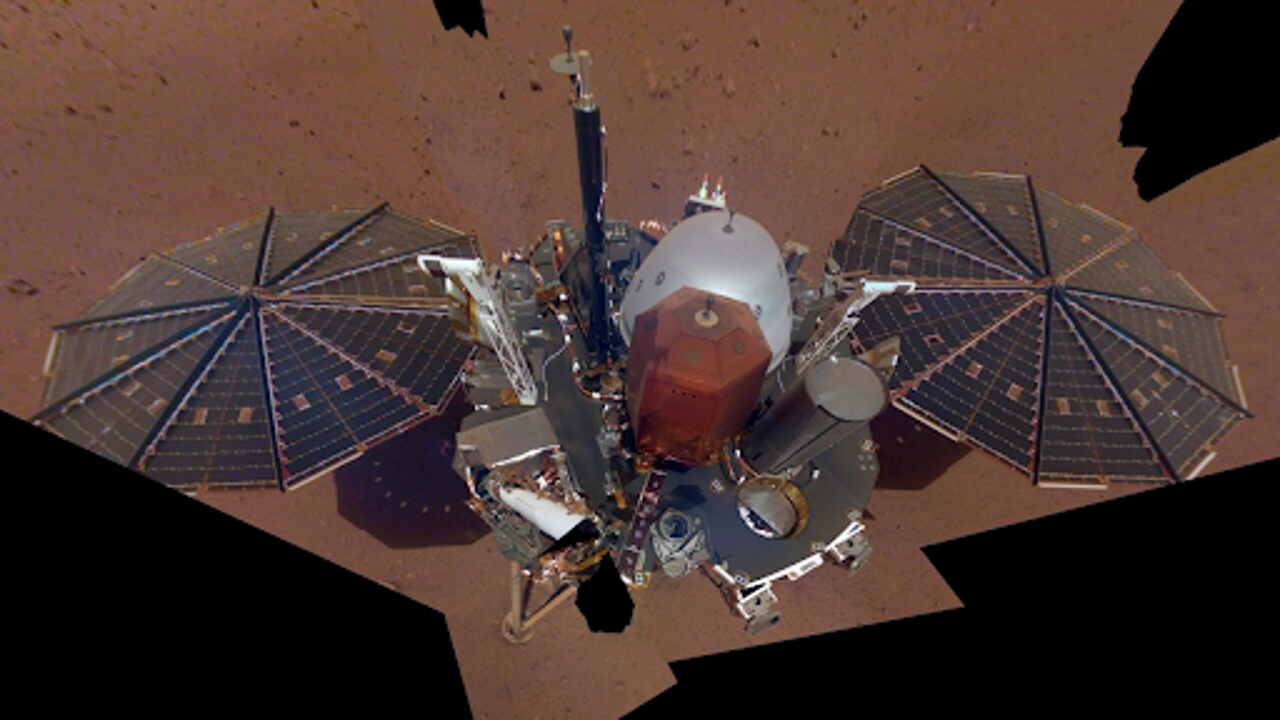

This photo, shared by NASA, shows the InSight Mars lander taking a selfie on April 24, 2022, marking its 1,211th day on the Martian surface. Source: NASA

New research suggests that Mars might have a vast amount of water hidden beneath its surface, possibly enough to form a global ocean. The study is based on seismic measurements taken by NASA’s Mars InSight lander, which detected over 1,300 marsquakes before it stopped functioning two years ago. These findings, published on Monday, have excited the scientific community as they offer new insights into the Red Planet’s history and potential habitability.

According to the study led by Vashan Wright of the University of California San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the water is likely trapped in cracks within underground rocks, lying between seven and 12 miles (11.5 to 20 kilometres) beneath the Martian crust. This water probably seeped from the surface billions of years ago when Mars had rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans. While the presence of water is intriguing, Wright cautioned that it doesn't necessarily mean Mars can support life. "Instead, our findings mean that there are environments that could possibly be habitable," Wright stated in an email.

The researchers used computer models combined with data from the InSight lander to arrive at their conclusion. The models, which analyzed the velocity of the marsquakes, indicated that underground water is the most plausible explanation for the seismic activity. These findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The InSight lander was positioned at Elysium Planitia near Mars’ equator, and if its findings are representative of the entire planet, Mars could have enough underground water to fill a global ocean one to two kilometres deep, Wright suggested. However, confirming the presence of this water and searching for any signs of microbial life would require drilling into the Martian crust, a task that would need sophisticated equipment and future missions.

Even though the InSight lander is no longer operational, the wealth of data it gathered between 2018 and 2022 continues to be analyzed by scientists eager to learn more about the planet's interior. Mars, which was likely wet and hospitable more than three billion years ago, gradually lost its surface water as its atmosphere thinned, transforming it into the dry, dusty world we see today. Some scientists believe that much of Mars' ancient water either escaped into space or remains buried below the surface, possibly in the form of ice or liquid water trapped in rock formations.